The first king of the Habsburg dynasty. Is the Habsburg dynasty the biblical Jews? The era of the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars

This term has other meanings, see Empire (meanings). Map of the Roman Empire at its peak Empire (from Latin imperium ... Wikipedia

- (empire); supreme power: Derived from the Latin imperator, which meant the highest military, and later political leader; later this word began to denote a territory, the exclusive right of power over which belonged to a single sovereign. ... ... Political science. Dictionary.

Austro-Hungarian Empire- (dual monarchy) (Austro Hungarian empire), the Habsburg empire in the period from 1867 to 1918. After the defeat in the war with Prussia (1866), the Austrian. Emperor Franz Joseph realized that the future of Austria should be strengthened on the banks of the Danube and in the Balkans. But… … The World History

German nation lat. Sacrum Imperium Romanum Nationis Germanicæ German. Heiliges Römisches Reich Deutscher Nation Empire ... Wikipedia

Territory of the Holy Roman Empire in 962 1806 The Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation (lat. Sacrum Imperium Romanum Nationis Teutonicae, German Heiliges Römisches Reich Deutscher Nation) is a state entity that has existed since 962 ... Wikipedia

Territory of the Holy Roman Empire in 962 1806 The Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation (lat. Sacrum Imperium Romanum Nationis Teutonicae, German Heiliges Römisches Reich Deutscher Nation) is a state entity that has existed since 962 ... Wikipedia

Territory of the Holy Roman Empire in 962 1806 The Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation (lat. Sacrum Imperium Romanum Nationis Teutonicae, German Heiliges Römisches Reich Deutscher Nation) is a state entity that has existed since 962 ... Wikipedia

Territory of the Holy Roman Empire in 962 1806 The Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation (lat. Sacrum Imperium Romanum Nationis Teutonicae, German Heiliges Römisches Reich Deutscher Nation) is a state entity that has existed since 962 ... Wikipedia

Monarquía universal española (Monarquía hispánica / Monarquía de España / Monarquía española) 1492 1898 ... Wikipedia

Books

- Ottoman Empire. Six centuries from rise to fall. XIV-XX centuries , Balfour John Patrick , The famous English writer and historian John Patrick Balfour on the pages of his book recreates the history of the Ottoman Empire from its founding at the turn of the XIII-XIV centuries. until the collapse in 1923. Authoritative ... Category: World history Series: Memorialis Publisher: Centerpoligraph,

- The Austro-Hungarian Empire, Shimov Yaroslav, The book is dedicated to the history of the formation, development and decline of a multinational state created by the Habsburg dynasty in the center of Europe at the beginning of the 16th century and existed until 1918 ... Category: History of foreign countries Series: World's Greatest Civilizations Publisher:

During the Middle Ages and the New Age, the Habsburgs, without exaggeration, were the most powerful royal house. From the modest owners of castles in the north of Switzerland and in Alsace, the Habsburgs turn into the rulers of Austria by the end of the 13th century.

According to legend, the culprit of the curse was Count Werner von Habsburg, who in the 11th century seduced the daughter of an ordinary artisan, swearing with all this that he would definitely marry her, although he was already engaged to another.

When the poor woman became pregnant, and the situation became fraught with scandal, the count, without hesitation, gave the order to deliver her, already on demolition, to his underground jail, chained to the wall and starved to death.

Having given birth to a baby and dying together with him in the dungeon, the woman cursed her own killer and his entire family, wishing that people would always remember him as the cause of misfortunes. The curse soon came true. Participating in a boar hunt with his young wife, Count Werner was mortally wounded by a feral boar.

Since that time, the power of the Habsburg curse either subsided for a while, then again made itself felt. In the 19th century, one of the last Habsburgs, Archduke Maximilian, brother of the Austro-Hungarian ruler Franz Joseph, arrived in Mexico City in 1864 as the founder of the newest Habsburg imperial line, ruled for only three years, after which the Mexicans revolted. Maximilian stood before a military court and was shot. His wife Carlota, daughter of the Belgian king, lost her mind and ended her days in a psychiatric hospital.

Video: Hour of Truth The Romanovs and the Habsburgs

Soon another offspring of Franz Joseph, Crown Prince Rudolf, went to the world: he committed suicide. Then, under mysterious circumstances, the wife of the ruler, whom he passionately adored, was killed.

The heir to the throne, Archduke Ferdinand of Habsburg, was shot dead in 1914 in Sarajevo together with his wife, which served as a specific pretext for the start of the First World War.

Well, for the last time, the curse that weighed on the Habsburg family made itself known 15 years after the events in Sarajevo. In April 1929, the Viennese police were obliged to break open the door of the apartment, from which came the acrid smell of lighting gas. Three corpses were found in the room, in which the guards identified the great-great-grandson of the ruler Franz Joseph, his mother Lena Resch and his grandmother. All three, as shown by the investigation, committed suicide ...

What was the curse

Overlord Carlos 2

The Habsburgs, as you know, ruled most of the states of Europe for more than five hundred years, owning all this time Austria, Belgium, Hungary, Germany and Holland. For 16 generations, the family has grown to 3 thousand people. And later, in the 18th century, it began to disappear.

According to Gonzalo Alvarez, doctor of the Institute of Santiago de Compostello, the Habsburgs were pursued by high infant mortality, despite the fact that they were already deprived of all the hardships of poverty and were under constant medical supervision.

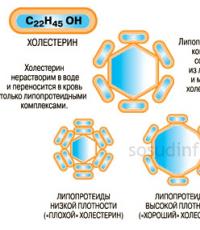

The Habsburgs were indeed tormented by the curse. But not from the magical, emphasizes Alvarez. It is well known that the curse of most royal families is marriages between relatives. So, hemophilia (blood incoagulability) until now, rightly or wrongly, is considered the “royal disease” caused by inbreeding, reports the CNews portal.

Dr. Gonzalo Alvarez states that the Habsburg dynasty suffered the most from inbreeding in Europe.

The crown of degradation was the Spanish ruler Carlos II, on whom Dr. Alvarez focuses his attention. The offspring of Philip the 4th, also a very sick person, he was ugly, suffered from intellectual deficiency and therefore had no chance of inheriting the crown, but his older brother, Balthazar Carlos, died at the age of 16, sending the freak to reign.

Carlos 2nd was marked by the “Hamburg lip” corresponding to most representatives of this family, a condition now called “mandibular prognathism” in medicine, the chin was very long, the tongue was very large, he spoke with difficulty and was drooling. He could not speak until 4, did not walk until 8, at 30 he looked like an old man, and at 39 he died without leaving an heir, as he was barren. He also suffered from convulsions and other disorders. In history, he is known as Carlos the Bewitched, since then it was believed that only sorceresses could bring on a similar state.

The Habsburg dynasty has been known since the 13th century, when its representatives owned Austria. And from the middle of the 15th century until the beginning of the 19th century, they completely retained the title of emperors of the Holy Roman Empire, being the most powerful monarchs of the continent.

History of the Habsburgs

The founder of the Habsburg family lived in the 10th century. There is almost no information about him today. It is known that his descendant, Count Rudolph, acquired land in Austria already in the middle of the 13th century. Actually, southern Swabia became their cradle, where the early representatives of the dynasty had a family castle. The name of the castle - Habischtsburg (from German - "hawk castle") and gave the name of the dynasty. In 1273 Rudolph was elected King of the Germans and Holy Roman Emperor.

He conquered Austria and Styria from King Premysl Otakar of the Czech Republic, and his sons Rudolf and Albrecht became the first Habsburgs to rule in Austria. In 1298, Albrecht inherits from his father the title of emperor and German king. And later his son was elected to this throne. However, throughout the 14th century, the title of Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire and King of the Germans was still elective among the German princes, and it did not always go to the representatives of the dynasty. Only in 1438, when Albrecht II becomes emperor, did the Habsburgs finally appropriate this title for themselves. Subsequently, there was only one exception, when the elector of Bavaria achieved the kingship by force in the middle of the 18th century.

Rise of a dynasty

Since this period, the Habsburg dynasty has been gaining more and more power, reaching brilliant heights. Their successes were laid down by the successful policy of Emperor Maximilian I, who ruled at the end of the 15th - beginning of the 16th century. Actually, his main successes were successful marriages: his own, which brought him the Netherlands, and his son Philip, as a result of which the Habsburg dynasty took possession of Spain. It was said about Maximilian's grandson, Charles V, that the Sun never sets over his possessions - his power was so widespread. He owned Germany, the Netherlands, parts of Spain and Italy, as well as some possessions in the New World. The Habsburg dynasty was at the height of its power.

However, even during the life of this monarch, the gigantic state was divided into parts. And after his death, it completely disintegrated, after which the representatives of the dynasty divided their possessions among themselves. Ferdinand I got Austria and Germany, Philip II - Spain and Italy. In the future, the Habsburgs, whose dynasty was divided into two branches, were no longer a single entity. In some periods, relatives even openly opposed each other. As was the case, for example, during the Thirty Years' War in

Europe. The victory of the reformers in it hit hard on the power of both branches. Thus, the emperor of the Holy Roman Empire never again had its former influence, which was associated with the formation of secular states in Europe. And the Spanish Habsburgs completely lost their throne, ceding it to the Bourbons.

In the middle of the 18th century, the Austrian rulers Joseph II and Leopold II for some time managed to once again raise the prestige and power of the dynasty. This second heyday, when the Habsburgs again became influential in Europe, lasted for about a century. However, after the revolution of 1848, the dynasty loses its monopoly of power even in its own empire. Austria becomes a dual monarchy - Austria-Hungary. Further - already irreversible - the process of disintegration was delayed only thanks to the charisma and wisdom of the reign of Franz Joseph, who became the last real ruler of the state. The Habsburg dynasty (photo of Franz Joseph on the right) after the defeat in the First World War was expelled in full force from the country, and on the ruins of the empire in 1919 a number of national independent states arose.

HABSBURG. Part 1. The Austrian branch of the Habsburgs

Emperors who made elective office hereditary.

The Habsburgs are a dynasty that ruled over the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation (until 1806), Spain (from 1516-1700), the Austrian Empire (formally from 1804) and Austria-Hungary (from 1867-1918).

The Habsburgs were one of the richest and most influential families in Europe. A distinctive feature of the appearance of the Habsburgs was an outstanding, slightly drooping lower lip.

Charles II Habsburg

The family castle of an old family, built at the beginning of the 11th century, was called Habsburg (from Habichtsburg - Hawk's Nest). From him the dynasty took its name.

Hawk's Nest Castle, Switzerland

The family castle of the Habsburgs - Schönbrunn - is located near Vienna. This is a modernized copy of the Versailles of Louis XIV, a significant part of the family and political life of the Habsburgs took place here.

Habsburg Summer Castle - Schönbrunn, Austria

And the main residence of the Habsburgs in Vienna was the Hofburg (Burg) palace complex.

Habsburg Winter Castle - Hofburg, Austria

In 1247, Count Rudolf of Habsburg was elected King of Germany, initiating a royal dynasty. Rudolf I annexed the lands of Bohemia and Austria to his possessions, which became the center of the dominion. The first emperor from the ruling Habsburg dynasty was Rudolf I (1218-1291), the German king from 1273. During his reign in 1273-1291, he took Austria, Styria, Carinthia and Kraina from the Czech Republic, which became the main core of the Habsburg possessions.

Rudolph I of Habsburg (1273-1291)

Rudolf I was succeeded by his eldest son Albrecht I, who was elected king in 1298.

Albrecht I Habsburg

Then, for almost a hundred years, representatives of other families occupied the German throne, until Albrecht II was elected king in 1438. Since then, representatives of the Habsburg dynasty have been constantly (with the exception of a single break in 1742-1745) elected kings of Germany and emperors of the Holy Roman Empire. A single attempt in 1742 to elect another candidate, the Bavarian Wittelsbach, led to civil war.

Albrecht II Habsburg

The Habsburgs received the imperial throne at a time when only a very strong dynasty could hold on to it. Through the efforts of the Habsburgs - Frederick III, his son Maximilian I and great-grandson Charles V - the highest prestige of the imperial title was restored, and the very idea of empire received a new content.

Friedrich III Habsburg

Maximilian I (emperor from 1493 to 1519) annexed the Netherlands to the Austrian possessions. In 1477, by marriage to Mary of Burgundy, he added Franche-Comté, a historic province in eastern France, to the Habsburgs. He married his son Charles to the daughter of the Spanish king, and thanks to the successful marriage of his grandson, he received rights to the Czech throne.

Emperor Maximilian I. Portrait by Albrecht Dürer (1519)

Bernhard Strigel. Portrait of Emperor Maximilian I and his family

Bernart van Orley. Young Charles V, son of Maximilian I. Louvre

Maximilian I. Portrait by Rubens, 1618

After the death of Maximilian I, three powerful kings claimed the imperial crown of the Holy Roman Empire - Charles V of Spain himself, Francis I of France and Henry VIII of England. But Henry VIII quickly renounced the crown, and Charles and Francis continued this struggle with each other almost all their lives.

In the struggle for power, Charles used the silver of his colonies in Mexico and Peru to bribe the electors and money borrowed from the richest bankers of that time, giving them the Spanish mines for this. And the electors elected the heir of the Habsburgs to the imperial throne. Everyone hoped that he would be able to resist the onslaught of the Turks and protect Europe from their invasion with the help of the fleet. The new emperor was forced to accept conditions according to which only Germans could hold public office in the empire, the German language was to be used on a par with Latin, and all meetings of state officials were to be held only with the participation of electors.

Charles V of Habsburg

Titian, Portrait of Charles V with his dog, 1532-33. Oil on canvas, Prado Museum, Madrid

Titian, Portrait of Charles V in an armchair, 1548

Titian, Emperor Charles V at the Battle of Mühlberg

So Charles V became the ruler of a huge empire, which included Austria, Germany, the Netherlands, southern Italy, Sicily, Sardinia, Spain and the Spanish colonies in America - Mexico and Peru. The “world power” under his rule was so great that the sun “never set” on it.

Even his military victories did not bring the desired success to Charles V. He proclaimed the creation of a "world Christian monarchy" as the goal of his policy. But internal strife between Catholics and Protestants destroyed the empire, the greatness and unity of which he dreamed of. During his reign, the Peasant War of 1525 broke out in Germany, the Reformation took place, and in Spain in 1520-1522 there was an uprising of the comuneros.

The collapse of the political program forced the emperor to eventually sign the Peace of Augsburg, and now each elector within his principality could adhere to the faith that he liked best - Catholic or Protestant, that is, the principle "whose power, that is the faith" was proclaimed. In 1556, he sent a message to the Electors with the renunciation of the imperial crown, which he ceded to his brother Ferdinand I (1556-64), who had been elected king of Rome back in 1531. In the same year, Charles V abdicated the Spanish throne in favor of his son Philip II and retired to a monastery, where he died two years later.

Emperor Ferdinand I of Habsburg in a portrait by Boxberger

Philip II of Habsburg in ceremonial armor

Austrian branch of the Habsburgs

Castile in 1520-1522 against absolutism. In the Battle of Villalar (1521), the rebels were defeated and in 1522 they stopped resisting. Government repression continued until 1526. Ferdinand I managed to secure for the Habsburgs the right to own the lands of the crown of St. Wenceslas and St. Stephen, which greatly increased the possessions and prestige of the Habsburgs. He tolerated both Catholics and Protestants, as a result of which the great empire actually broke up into separate states.

Already during his lifetime, Ferdinand I ensured the succession by holding an election for the Roman king in 1562, which was won by his son Maximilian II. He was an educated man with gallant manners and deep knowledge of modern culture and art.

Maximilian II of Habsburg

Giuseppe Arcimboldo. Portrait of Maximilian II with his family, c. 1563

Maximilian II causes very contradictory assessments of historians: he is both a “mysterious emperor”, and a “tolerant emperor”, and a “representative of the humanistic Christianity of the Erasmus tradition”, but recently he is most often called the “emperor of the religious world”. Maximilian II of Habsburg continued the policy of his father, who sought to find compromises with the opposition-minded subjects of the empire. This position provided the emperor with extraordinary popularity in the empire, which contributed to the unhindered election of his son, Rudolph II, as king of Rome, and then emperor.

Rudolf II Habsburg

Rudolf II Habsburg

Rudolf II was brought up at the Spanish court, had a deep mind, strong will and intuition, was far-sighted and reasonable, but for all that he was timid and prone to depression. In 1578 and 1581 he suffered serious illnesses, after which he stopped appearing at hunting, tournaments and festivities. Over time, suspicion developed in him, and he became afraid of witchcraft and poisoning, sometimes he thought about suicide, and in recent years he sought oblivion in drunkenness.

Historians believe that bachelor life was the cause of his mental illness, but this is not entirely true: the emperor had a family, but not consecrated by marriage. He was in a long relationship with the daughter of the antiquarian Jacopo de la Strada Maria, and they had six children.

The favorite son of the emperor, Don Julius Caesar of Austria, was mentally ill, committed a brutal murder and died in custody.

Rudolf II of Habsburg was an extremely versatile enthusiastic person: he loved Latin poetry, history, devoted a lot of time to mathematics, physics, astronomy, was interested in the occult sciences (there is a legend that Rudolf had contacts with Rabbi Lev, who allegedly created the "Golem", an artificial man) . During his reign, mineralogy, metallurgy, zoology, botany and geography received significant development.

Rudolf II was the largest collector in Europe. His passion was the work of Dürer, Pieter Brueghel the Elder. He was also known as a watch collector. And the culmination of his encouragement of jewelry art was the creation of a magnificent imperial crown - a symbol of the Austrian Empire.

Personal crown of Rudolf II, later crown of the Austrian Empire

He showed himself as a talented commander (in the war with the Turks), but could not take advantage of the fruits of this victory, the war took on a protracted character. This caused an uprising in 1604, and in 1608 the emperor abdicated in favor of his brother Matthias. I must say that Rudolf II resisted such a turn of affairs for a long time and stretched out the transfer of powers to the heir for several years. This situation tired both the heir and the population. Therefore, everyone breathed a sigh of relief when Rudolf II died of dropsy on January 20, 1612.

Matthias Habsburg

Mattias got only the appearance of power and influence. The finances in the state were completely upset, the foreign policy situation was steadily leading to a big war, domestic politics threatened another uprising, and the victory of the irreconcilable Catholic party, at the origins of which Matthias stood, actually led to his overthrow.

This unhappy legacy went to Ferdinand of Central Austria, who was elected Roman Emperor in 1619. He was a friendly and generous gentleman to his subjects and a very happy husband (in both of his marriages).

Ferdinand II Habsburg

Ferdinand II loved music and loved hunting, but his work came first. He was deeply religious. During his reign, he successfully overcame a number of difficult crises, he managed to unite the politically and confessionally divided possessions of the Habsburgs and begin a similar unification in the empire, which was to be completed by his son, Emperor Ferdinand III.

Ferdinand III Habsburg

The most important political event of the era of the reign of Ferdinand III is the Peace of Westphalia, with the conclusion of which the Thirty Years' War ended, which began as an uprising against Matthias, continued under Ferdinand II and stopped by Ferdinand III. By the time peace was signed, 4/5 of all war resources were in the hands of the emperor's opponents, and the last parts of the imperial army capable of maneuvering were defeated. In this situation, Ferdinand III proved himself to be a firm politician, able to independently make decisions and consistently implement them. Despite all the defeats, the emperor perceived the Peace of Westphalia as a success that prevented even more serious consequences. But the treaty, signed under pressure from the electors, which brought peace to the empire, at the same time undermined the authority of the emperor.

The prestige of the emperor's power had to be restored by Leopold I, who was elected in 1658 and then ruled for 47 years. He was able to successfully play the role of the emperor as the defender of law and order, step by step restoring the authority of the emperor. He worked long and hard, leaving the empire only when necessary, and made sure that strong personalities did not occupy a dominant position for a long time.

Leopold I Habsburg

The alliance concluded in 1673 with the Netherlands allowed Leopold I to strengthen the foundations for the future position of Austria as a great European power and to achieve its recognition among the electors - subjects of the empire. Austria again became the center around which the empire was defined.

Under Leopold, Germany experienced a revival of Austrian and Habsburg hegemony in the empire, the birth of the "Viennese imperial baroque". The emperor himself was known as a composer.

Leopold I of Hasburg was succeeded by Emperor Joseph I of Habsburg. The beginning of his reign was brilliant, and a great future was predicted for the emperor, but his undertakings were not completed. Soon after his election, it became clear that he preferred hunting and amorous adventures to serious work. His affairs with the ladies of the court and with the maids brought a lot of worries to his respectable parents. Even an attempt to marry Joseph was unsuccessful, because the wife could not find the strength in herself to tie the indefatigable hubby.

Joseph I of Habsburg

Joseph died of smallpox in 1711, remaining in history as a symbol of hope, which was not destined to come true.

Charles VI became the emperor of Rome, who had previously tried his hand as King Charles III of Spain, but was not recognized by the Spaniards and was not supported by other rulers. He managed to maintain peace in the empire without dropping the authority of the emperor.

Charles VI of Habsburg, last of the Habsburgs in the male line

However, he was unable to ensure the succession of the dynasty, since there was no son among his children (he died in infancy). Therefore, Charles took care to regulate the order of succession. A document was adopted, known as the Pragmatic Sanction, according to which, after the complete extinction of the ruling branch, the daughters of his brother, and then his sisters, first receive the right to inherit. This document contributed in no small measure to the rise of his daughter Maria Theresa, who ruled the empire first with her husband, Francis I, and then with her son, Joseph II.

Maria Theresa at age 11

But not everything was so smooth in history: with the death of Charles VI, the Habsburg male line was interrupted, and Charles VII of the Wittelsbach dynasty was elected emperor, which made the Habsburgs remember that the empire is an elective monarchy and its management is not connected with a single dynasty.

Portrait of Maria Theresa

Maria Theresa attempted to return the crown to her family, which she succeeded after the death of Charles VII - her husband, Franz I, became emperor. However, in fairness, it should be noted that Franz was not an independent politician, for all affairs in the empire were taken over by him indefatigable wife. Maria Theresa and Franz were happily married (despite Franz's numerous infidelities, which his wife preferred not to notice), and God rewarded them with numerous offspring: 16 children. Surprisingly, it is a fact: the Empress even gave birth, as it were, between times: she worked with documents until the doctors sent her to the maternity room, and immediately after the birth she continued to sign documents and only after that she could afford to rest. She entrusted the care of raising children to trusted persons, strictly controlling them. Interest in the fate of children really manifested itself in her only when it was time to think about the arrangement of their marriages. And here Maria Theresa showed truly remarkable abilities. She arranged the weddings of her daughters: Marie-Caroline married the King of Naples, Marie-Amelia married the Infante of Parma, and Marie Antoinette, married the Dauphin of France Louis (XVI), became the last queen of France.

Maria Theresa, who pushed her husband's big politics into the shadows, did the same with her son, which is why their relationship has always been tense. As a result of these skirmishes, Joseph preferred to travel.

Franz I Stephen, Francis I of Lorraine

During his trips he visited Switzerland, France, Russia. Travel not only expanded the circle of his personal acquaintances, but also increased his popularity with his subjects.

After the death of Maria Theresa in 1780, Joseph was finally able to carry out the reforms that he had considered and prepared while still under his mother. This program was born, run and died with him. Joseph was alien to dynastic thinking, he sought to expand the territory and pursue the Austrian great-power policy. This policy turned almost the entire empire against him. Nevertheless, Joseph managed to still achieve some results: in 10 years he changed the face of the empire so much that only descendants could truly appreciate his work.

Joseph II, eldest son of Maria Theresa

It was clear to the new monarch, Leopold II, that only concessions and a slow return to the past would save the empire, but with the clarity of goals, he had no clarity in actually achieving them, and, as it turned out later, he also did not have time, because the emperor died 2 years after the election.

Leopold II, third son of Francis I and Maria Theresa

Franz II ruled for over 40 years, under him the Austrian Empire was formed, under him the final collapse of the Roman Empire was recorded, under him Chancellor Metternich ruled, after whom an entire era is named. But the emperor himself in the historical light appears as a shadow leaning over government papers, a vague and amorphous shadow, incapable of independent body movements.

Franz II with scepter and crown of the new Austrian Empire. Portrait by Friedrich von Amerling. 1832. Museum of the History of Art. Vein

At the beginning of the reign, Franz II was a very active politician: he carried out management reforms, mercilessly changed officials, experimented in politics, and many simply took their breath away from his experiments. It is later that he will become a conservative, suspicious and unsure of himself, unable to make global decisions ...

Franz II assumed the title of hereditary emperor of Austria in 1804, which was associated with the proclamation of Napoleon as hereditary emperor of the French. And by 1806, circumstances were developing in such a way that the Roman Empire turned into a ghost. If in 1803 there were still some remnants of the imperial consciousness, now they were not even remembered. Soberly assessing the situation, Franz II decided to lay down the crown of the Holy Roman Empire and from that moment devoted himself entirely to strengthening Austria.

In his memoirs, Metternich wrote about this turn of history: "Franz, deprived of the title and those rights that he had before 1806, but incomparably more powerful than then, was now the true emperor of Germany."

Ferdinand I of Austria "The Good" occupies a modest place between his predecessor and his successor, Franz Joseph I.

Ferdinand I of Austria "The Good"

Ferdinand I enjoyed great popularity among the people, as evidenced by numerous anecdotes. He was a supporter of innovations in many areas: from the laying of the railway to the first long-distance telegraph line. By decision of the emperor, the Military Geographic Institute was created and the Austrian Academy of Sciences was founded.

The emperor was ill with epilepsy, and the disease left its mark on his attitude. He was called “blissful”, “fool”, “stupid”, etc. Despite all these unflattering epithets, Ferdinand I showed various abilities: he knew five languages, played the piano, was fond of botany. In the management of the state, he also achieved some success. So, during the revolution of 1848, it was he who realized that the Metternich system, which had been successfully working for many years, had become obsolete and needed to be replaced. And Ferdinand Joseph had the firmness to refuse the services of the Chancellor.

In the difficult days of 1848, the emperor tried to resist the circumstances and the pressure of those around him, but he was eventually forced to abdicate, followed by the abdication of Archduke Franz Karl. Franz Joseph, the son of Franz Karl, became emperor, who ruled Austria (and then Austria-Hungary) for no less than 68 years. The first years the emperor ruled under the influence, if not under the leadership, of his mother, Empress Sophia.

Franz Joseph in 1853. Portrait by Miklós Barabash

Franz Joseph I of Austria

For Franz Joseph I of Austria, the most important things in the world were: the dynasty, the army and religion. The young emperor at first zealously set to work. Already in 1851, after the defeat of the revolution, the absolutist regime in Austria was restored.

In 1867, Franz Joseph transformed the Austrian Empire into the dual monarchy of Austria-Hungary, in other words, he made a constitutional compromise that retained for the emperor all the advantages of an absolute monarch, but at the same time left unresolved all the problems of the state system.

The policy of coexistence and cooperation among the peoples of Central Europe is the tradition of the Habsburgs. It was a conglomeration of peoples, in fact, equal in rights, because everyone, be it a Hungarian or a Bohemian, a Czech or a Bosnian, could take any public post. They ruled in the name of the law and did not take into account the national origin of their subjects. For the nationalists, Austria was a "prison of peoples", but, oddly enough, the people in this "prison" grew rich and prospered. Thus, the House of Habsburg realistically assessed the benefits of having a large Jewish community in Austria and invariably defended the Jews from the attacks of Christian communities - so much so that anti-Semites even called Franz Joseph the "Jewish Emperor."

Franz Joseph loved his charming wife, but on occasion he could not resist the temptation to admire the beauty of other women, who usually reciprocated. He also could not resist gambling, often visiting the casinos of Monte Carlo. Like all Habsburgs, the emperor under no circumstances misses the hunt, which has a pacifying effect on him.

The Habsburg Monarchy was swept away by the whirlwind of revolution in October 1918. The last representative of this dynasty, Charles I of Austria, was overthrown, having been in power for only about two years, and all the Habsburgs were expelled from the country.

Charles I of Austria

The last representative of the Habsburg dynasty in Austria - Charles I of Austria with his wife

There was an ancient legend in the Habsburg family: the proud family will begin with Rudolf and end with Rudolf. The prediction almost came true, for the dynasty fell after the death of Crown Prince Rudolf, the only son of Franz Joseph I of Austria. And if the dynasty held out on the throne after his death for another 27 years, then for a prediction made many centuries ago, this is an insignificant error.

The national question and the crisis of the monarchy

The nature and characteristics of the revolutionary process in the Habsburg Monarchy determined the large number of peoples inhabiting it and the inconsistency of their socio-economic and political goals. In 1843, a little over 29 million people inhabited the territory of the empire. Of these, 15.5 million were Slavic peoples, there were 7 million Germans, 5.3 million Hungarians, 1 million Romanians, and 0.3 million Italians. (Czech Republic), Galicia, Silesia, Slovenia, Dalmatia, Italians of the Lombardo-Venetian region. The Magyars of Hungary, seeking to restore the lost statehood and being in connection with this in a state of conflict with the Habsburgs, themselves suppressed the Rusyns of Transcarpathia, Slovaks, the southern Slavs of Croatia and Slavonia, the Serbs of Vojvodina, and the Romanians of Transylvania, placed in administrative dependence on them. In the lands of the Hungarian crown, the Magyars not only held the administrative apparatus in their hands, but also concentrated a significant part of landed property, collecting feudal duties from the peasants.The inequality of the peoples of the empire put forward the objective task of national revival. Therefore, bourgeois transformations, which meant for Austria the destruction of the remnants of feudal economic relations and the transition from an absolutist to a constitutional form of government, in other parts of the empire led not only to the same result, but also to the establishment of their own statehood. The latter threatened the collapse of the Habsburg monarchy. It is not surprising that the Vienna court and Chancellor Metternich considered the stability of the established foundations, bureaucratic management, unlimited police control over the activities of the intelligentsia, and total supervision of the press to be the basis for maintaining the empire. The suppression of glasnost went as far as banning the publication of books of political content and the importation of liberal writings from England and France, even if they did not fall into the index of banned books compiled by the Roman Curia.

The development of the state was hampered by ossified political structures. Since 1835, Ferdinand 1 was emperor, periodically plunging into a severe depression. Under him, the triumvirate (from Latin triumviratus - three + + husband) was in charge of all affairs: the uncle of the emperor, Archduke Ludwig, Prince Metternich and Count Kolovrat. The rivalry between them made it impossible to make the necessary decisions. This had detrimental consequences for the monarchy, as the situation in the country became more and more tense. Despite the police regime, the reform movement was expanding in the empire. The bourgeois nobility, the bourgeoisie and the intelligentsia came forward with demands for their implementation. These social strata were interested in capitalist transformations. Remaining moderately oppositional and liberal, they sought a transition to a constitutional monarchy, the abolition of feudal duties for the ransom, and the abolition of workshops. Consolidation of supporters of reforms led to the creation of several organizations: "Political and Legal Club", "Industrial Union", "Lower Austrian Industrial Association", writers' union "Concordia". Opposition literature circulated in Vienna and the provinces.

Revolution of 1848 in Austria

In February 1848, when news of the revolution in France became known, the muffled unrest grew into actions of direct pressure on the government. During March 3-12, a group of deputies of the Landtag of Lower Austria, which included Vienna, the "Industrial Union", university students presented, although at different times and separately, but essentially similar demands: to convene an all-Austrian parliament, reorganize the government, abolish censorship and introduce freedom words. The government hesitated, and on March 13 the building of the Landtag was surrounded by crowds of people, slogans sounded: "Down with Metternich ... The Constitution ... People's Representation." Clashes initiated by people from the crowd with the troops that entered the city began, the first victims appeared. It came to the barricades, and the students also created a paramilitary organization - the Academic Legion. Soon the formation of the national guard began from people who had "property and education", i.e. bourgeoisie.The Academic Legion and the National Guard formed committees that began to actively intervene in the events that were taking place. The balance of power changed, and the emperor was forced to agree to arm the bourgeois formations, dismissed Metgernich and sent him as ambassador to London. The government proposed a draft constitution, but Bohemia (Czech Republic) and Moravia refused to recognize it. In turn, the Vienna committees of the Academic Legion and the National Guard regarded this document as an attempt to preserve absolutism and responded by creating a joint Central Committee. The government's decision to dissolve it was followed by a barricade-backed demand for the withdrawal of troops from Vienna, the introduction of universal suffrage, the convening of a Constituent Assembly and the adoption of a democratic constitution. The government again retreated and promised to fulfill all this, but at the insistence of the emperor, it did the opposite: it issued an order to disband the Academic Legion. The people of Vienna responded with new barricades and the creation on May 26, 1848 of a Committee of Public Safety made up of municipal councilors, national guardsmen and students. He took upon himself the maintenance of order and control over the fulfillment by the government of its obligations. The influence of the Committee extended so far that it insisted on the resignation of the Minister of the Interior and proposed the composition of a new government, which included representatives of the liberal bourgeoisie.

The impotence of the imperial court was forced to reconcile. The emperor himself was not in Vienna at that time; on May 17, without even notifying the ministers, he left for Innsbruck, the administrative center of Tyrol. The Vienna garrison barely numbered 10,000 soldiers. The main part of the army, led by Field Marshal Vindischgrätz, was busy suppressing the uprising that began on June 12, 1848 in Prague, and then got stuck in Hungary. The best troops of Field Marshal Radetzky in Austria pacified the rebellious Lombardo-Venetian region and fought with the army of Sardinia, which tried to take advantage of the favorable moment and annex the Italian possessions of Austria.

Nothing could prevent the holding of elections to the first Austrian Reichstag, they took place and gave the majority to the representatives of the liberal bourgeoisie and the peasantry. This composition determined the nature of the adopted laws:

feudal duties, and personal seigneurial rights (suzerain power, patrimonial court) without remuneration, and duties related to land use (corvée, tithe) - for a ransom. The state undertook to reimburse a third of the redemption sum, the rest was to be paid by the peasants themselves. The abolition of feudal relations opened the way for the development of capitalism in agriculture. The solution of the agrarian question had the consequence that the peasantry departed from the revolution. The stabilization of the situation allowed Emperor Ferdinand I to return to Vienna on August 12, 1848.

The last major uprising of the masses of Vienna took place on October 6, 1848, when students from the Academic Legion, national guards, workers, and artisans tried to prevent the sending of part of the Vienna garrison to suppress the uprising in Hungary. In the course of street fighting, the rebels took possession of the arsenal, seized weapons, broke into the War Ministry and hung Minister Baie de Latour from a street lamp.

The day after these events, Emperor Ferdinand I fled to Olmutz, a powerful fortress in Moravia, and Windischgrätz, having thrown back the Hungarian revolutionary army hurrying to Vienna, after three days of fighting on November 1, 1848, occupied the Austrian capital. The critical situation allowed the upper echelons of power to achieve the abdication of Ferdinand in favor of the nephew Franz Joseph, who ascended the throne on December 2, 1848 and remained emperor for 68 years, until 1916. called Olmutsskaya. It applied to both Austria and Hungary, proceeded from the principle of the integrity and indivisibility of the state, but was never put into practice and was formally abolished on December 31, 1851.

Revolution of 1848-1849 in Hungary

The revolutionary wave in March 1848 also swept over Hungary. At the beginning of the monththe leader of the noble opposition, Lajos Kossuth, proposed to the Sejm a program of bourgeois-democratic reforms. It provided for the adoption of the Hungarian constitution, the implementation of reforms, the appointment of a government responsible to the parliament. In Pest, demonstrations and rallies began in support of the reforms. On March 15, 1848, students, artisans, workers, led by the poet Sandor Petofi, seized the printing house and printed a list of demands - “12 points”, among which one of the main ones were: freedom of speech and press, a national government, the withdrawal of non-Hungarian military units from the country and the repatriation of the Hungarians, the unification of Transylvania and Hungary.

The laws adopted by the Sejm, bourgeois in content, provided for the abolition of corvée and church tithes. Peasants who had corvee plots (and they accounted for about a third of all cultivated land) received them as their property. The issue of redemption payments was postponed for the future. Although only about 600,000 of the 1.5 million peasants liberated by the revolution became land owners, the agrarian reform undermined the feudal serf system in Hungary. The constitutional reform preserved the monarchy, but transformed the political system of the country, which was reflected in the establishment of a government responsible to the parliament, the expansion of suffrage and the annual convocation of the Seimas, the introduction of a jury, and the establishment of freedom of the press. In the field of national relations, a complete merger with Transylvania and the recognition of the Magyar language as the only state language were envisaged. On March 17, 1848, the first independent government of Hungary began its activities. It was headed by one of the leaders of the opposition, Count Lajos Batteanu, and Kossuth, who took the post of finance minister, played an influential role in the cabinet. Emperor Ferdinand I (in Hungary he bore the title of King Ferdinand V) at first tried to cancel the laws adopted by the Sejm, but mass demonstrations in Pest and in Vienna itself forced him to approve the Hungarian reforms in early April.

At the same time, the Hungarian nobility, out of fear of losing their dominant position in the kingdom and the collapse of it itself, opposed the national movements. Therefore, the government did nothing in the specific interests of the Slavic and Romanian territories of the Hungarian crown. The refusal to recognize their national equality, to grant self-government, to guarantee the free development of language and culture, turned the national movements, originally sympathetic to the Hungarian revolution, into allies of the Habsburg Monarchy.

This trend turned out to be dominant in all non-Magyar lands subject to Hungary. Convened on March 25, 1848, the Croatian Estates Seim - Sabor developed a program that provided for the abolition of feudal duties, the creation of an independent government and its own army, the introduction of the Croatian language in administrative institutions and courts. The answer to the great-power policy of Hungary, which deprived Croatia of any rights to autonomy, was the decision taken by the Sabor in June 1848 to recreate Croatian statehood in the form of the Croatian-Slavono-Dalmatian kingdom under the supreme authority of the Habsburgs. The interethnic conflict led to a war with Hungary, which was started in September 1848 by the Croatian ban Josip Jelacic.

The Hungarian-Croatian clash did not end the ethnic contradictions. When Slovakia demanded to recognize the Slovak language as an official language, to open a Slovak university and schools, to provide territorial autonomy with its own Sejm, the Hungarian government only intensified repression. Regarding the national problems of the Serbs, Kossuth stated that "the dispute will be decided by the sword." The non-recognition of the rights of the Serbs led to the proclamation in May 1848 of the "Serbian Vojvodina" with its own government and the ensuing attempt by the Hungarians to suppress the Serbian movement by force. The Austrian Habsburgs, recognizing the separation of Vojvodina from Hungary, turned this clash to their advantage. The Hungarian law on union with Transylvania, which recognized only the personal equality of its citizens, but did not establish national-territorial autonomy, and here provoked an anti-Magyar uprising that began in mid-September 1848.

Hungary's desire for independence provoked sharp opposition from Emperor Ferdinand, who on September 22, 1848 issued a statement that was regarded as a declaration of war. In order to better prepare for it, the Hungarians rebuilt the leadership: the Batteanu government resigned and gave way to the Defense Committee, headed by Kossuth. The national army he created defeated the troops of Elachich, pushed them back to the borders of Austria, and then itself entered Austrian territory. This success was short-lived. On October 30, in a battle near Vienna, the Hungarians were defeated. In mid-December, the army of Windischgrätz transferred hostilities to Hungary and in January 1849 captured its capital.

Military failures did not force Hungary to submit. Moreover, after the abdication of Ferdinand, the Diet refused to consider Franz Joseph the king of Hungary until he recognized the Hungarian constitutional order. The Hungarian constitution did not meet the ideas of the Viennese court about the state structure of the empire, and this, along with Austrian internal political factors proper, prompted Franz Joseph to establish, as already noted, the Olmutz constitution. According to it, Hungary lost all independence and moved to the position of a province of the Habsburg Empire, which did not suit the Hungarian nobility and the bourgeoisie at all. As a consequence, on April 14, 1849, the Diet of Hungary deposed the Habsburg dynasty, proclaimed the independence of Hungary and elected Kossuth as head of the executive branch with the status of ruler. Now the Austro-Hungarian conflict could only be resolved by force of arms.

In the spring of 1849, the Hungarian troops won a number of victories. Their commander, General Artur Görgey, is believed to have been able to capture the virtually defenseless Vienna, but was bogged down in a lengthy siege of Buda. Opinions are expressed that Gergely claimed the first role and, not content with the position of Minister of War and Commander-in-Chief, betrayed the cause of the revolution. Like it or not, the Austrian monarchy got a break, and Emperor Franz Joseph turned to the Russian Emperor Nicholas I with a request for help.

The invasion in June 1849 of the 100,000th army of Field Marshal Paskevich into Hungary and the 40,000th corps into Transylvania predetermined the defeat of the Hungarian revolution. She was no longer able to help the hopelessly late law on the equality of the peoples inhabiting the Hungarian state. On August 13, 1849, the main forces of the Hungarian army, together with Görgey, laid down their arms. In the course of the repressions, the courts-martial issued about 500 death sentences. They saved Görgey's life, however, sending him to prison for 20 years, but the head of the first government, Battyanu, and 13 generals of the Hungarian army were executed. Kossuth emigrated to Turkey.

The results of the revolution of 1848-1849. in the Habsburg Monarchy

The defeat of the revolution led to the restoration of absolutism in the empire, but its restoration was not complete. The abolition of feudal duties was the largest socio-economic transformation in connection with the emergence of a class of independent peasant owners. A return to the old feudal order became impossible.At the same time, a period of most severe reaction set in in the national-political sphere. The abolition of Austro-Hungarian dualism led to the subordination of Hungarian officials to a military and civil governor appointed by Vienna. The territory of Hungary proper was divided into five imperial governorships. Transylvania, Croatia-Slavonia, Serbian Vojvodina and Temishvar Banat, previously administratively subordinate to Hungary, were placed under direct Austrian control. Throughout the empire, police oversight was strengthened, and a corps of gendarmes was created to oversee political reliability. The Law on Unions and Assemblies placed public organizations under the strictest control of the authorities. All periodicals were required to pay a deposit and submit one copy to the authorities an hour before publication. Retail sale and posting of newspapers on the streets was banned. The Germanization of the empire intensified. The German language was declared the state language and obligatory for administration, legal proceedings, public education in all parts of the empire. The unresolved national and democratic tasks throughout the subsequent time will constantly put the empire in front of the need to overcome the growing political crises until, under their weight, it collapses completely.

Asya Golverk, Sergey Khaimin

Compiled based on materials from the Encyclopedias Britannica, Larousse, Around the World, etc.

Roman era

Very little is known about the first inhabitants of Austria. Scant historical evidence suggests the existence of a pre-Celtic population. Around 400–300 BC militant Celtic tribes appeared with their own dialect, religious cults and traditions. Mixing with the ancient inhabitants, the Celts formed the kingdom of Norik.

At the beginning of the II century. BC. Roman power extended to the Danube. However, the Romans were forced to constantly fight against the nomadic Germanic barbarians who invaded from the north across the Danube, which served as the border of Roman civilization. The Romans built fortified military camps at Vindobona (Vienna) and at Carnunte, 48 km from the first; in the Hoher Markt district of Vienna, remains of Roman buildings have been preserved. In the region of the middle Danube, the Romans contributed to the development of cities, crafts, trade and the ore industry, built roads and buildings. Emperor Marcus Aurelius (died at Vindobona in 180 AD) composed part of his immortal Meditations at Carnuntum. The Romans implanted among the local population religious pagan rites, secular institutions and customs, the Latin language and literature. By the 4th c. is the Christianization of this region.

In the 5th and 6th centuries Germanic tribes overran most of the Roman possessions in the western part of modern Austria. The eastern and southern parts of modern Austria were invaded by Turkic-speaking nomads - the Avars, along with them (or after them) the Slavic peoples migrated - the future Slovenes, Croats and Czechs, among whom the Avars disappeared. In the western regions, missionaries (Irish, Franks, Angles) converted pagan Germans (Bavarians) to Christianity; The cities of Salzburg and Passau became the centers of Christian culture. Around 774, a cathedral was built in Salzburg, and by the end of the 8th century. the local archbishop was given authority over neighboring dioceses. Monasteries were built (for example, Kremsmünster), and the conversion of the Slavs to Christianity began from these islands of civilization.

The invasion of the Hungarians in the Eastern March

Charlemagne (742-814) defeated the Avars and began to encourage the German colonization of the Eastern March. German settlers received privileges: they were given land allotments, which were processed by slaves. Cities on the Middle Danube flourished again.

Frankish rule in Austria ended abruptly. The Carolingian Empire was ruthlessly devastated by the Hungarians. These warlike tribes were destined to have a lasting and profound influence on the life of the middle part of the Danube valley. In 907, the Hungarians captured the Eastern March and from here carried out bloody raids on Bavaria, Swabia and Lorraine.

Otto I, German emperor and founder of the Holy Roman Empire (962), defeated a powerful Hungarian army in 955 on the Lech River near Augsburg. Pushed east, the Hungarians gradually settled downstream in the fertile Hungarian Plain (where their descendants still live) and adopted the Christian faith.

Board of the Babenbergs

The place of the expelled Hungarians was taken by German settlers. The Bavarian Eastern Mark, which at that time covered the area around Vienna, was transferred in 976 as a fief to the Babenberg family, whose family estates were located in the Main valley in Germany. In 996, the territory of the East March was first named Ostarriki.

One of the prominent representatives of the Babenberg dynasty was the macrograve Leopold III (reigned 1095–1136). The ruins of his castle on the Leopoldsberg mountain near Vienna have been preserved. Nearby is the monastery of Klosterneuburg and the majestic Cistercian abbey in Heiligenstadt, the burial place of the Austrian rulers. The monks in these monasteries cultivated the fields, taught the children, wrote chronicles and looked after the sick, greatly contributing to the enlightenment of the surrounding population.

German settlers completed the development of the Eastern Mark. The methods of cultivating the land and growing grapes were improved, and new villages were founded. Many castles were built along the Danube and inland, such as Dürnstein and Aggstein. During the period of the Crusades, the cities prospered, and the wealth of the rulers grew. In 1156, the emperor conferred the title of duke on Henry II, Margrave of Austria. The land of Styria, south of Austria, was inherited by the Babenbergs (1192), while parts of Upper Austria and Krotna were acquired in 1229.

Austria entered its heyday during the reign of Duke Leopold VI, who died in 1230, having become famous as a merciless fighter against heretics and Muslims. Monasteries were showered with generous gifts; the newly created monastic orders, the Franciscans and Dominicans, were cordially received in the duchy, and poets and singers were encouraged.

Vienna, long in decline, in 1146 became the residence of the duke; great benefit was derived from the development of trade through the Crusades. In 1189, it was first mentioned as a civitas (city), in 1221 it received city rights and in 1244 confirmed them, having received formal city privileges that determined the rights and obligations of citizens, regulated the activities of foreign merchants and provided for the formation of a city council. In 1234, a more humane and enlightened law on their rights was issued for the Jewish residents than in other places, which remained in force until the expulsion of the Jews from Vienna almost 200 years later. At the beginning of the XIII century. the boundaries of the city were expanded, new fortifications arose.

The Babenberg dynasty died out in 1246, when Duke Frederick II died in battle with the Hungarians, leaving no heirs. The struggle for Austria, an economically and strategically important territory, began.

Strengthening of the Austrian state under the Habsburgs

The Pope handed over the vacant throne of the duchy to Margrave Hermann of Baden (reigned 1247-1250). However, the Austrian bishops and the feudal nobility elected the Bohemian king Přemysl II (Otakar) (1230–1278) (1230–1278) as duke, who reinforced his rights to the Austrian throne by marrying the sister of the last Babenberg. Přemysl captured Styria and received Carinthia and part of Carniola by marriage contract. Premysl sought the crown of the Holy Roman Empire, but on September 29, 1273, Count Rudolf of Habsburg (1218–1291), respected both for his political prudence and for his ability to avoid disputes with the papacy, was elected king. Přemysl refused to recognize his election, so Rudolph resorted to force and defeated his rival. In 1282, one of the key dates in Austrian history, Rudolph declared the lands of Austria that belonged to him to be hereditary possession of the House of Habsburg.

From the very beginning, the Habsburgs considered their lands to be private property. Despite the struggle for the crown of the Holy Roman Empire and family strife, the dukes from the house of Habsburg continued to expand the boundaries of their possessions. An attempt had already been made to annex the land of Vorarlberg in the southwest to it, but this was only completed by 1523. Tyrol was annexed to the possessions of the Habsburgs in 1363, as a result of which the Duchy of Austria came close to the Apennine Peninsula. In 1374, a part of Istria was attached to the northern tip of the Adriatic Sea, and after 8 years the port of Trieste voluntarily joined Austria in order to free itself from the rule of the Venetians. Representative (estate) assemblies were created, consisting of nobles, clergy and townspeople.

Duke Rudolf IV (reigned 1358-1365) made plans to annex the kingdoms of Bohemia and Hungary to his possessions and dreamed of achieving complete independence from the Holy Roman Empire. Rudolph founded the University of Vienna (1365), financed the expansion of the Cathedral of St. Stephen and supported trade and crafts. He died suddenly, without realizing his ambitious plans. Under Rudolph IV, the Habsburgs began to bear the title of archdukes (1359).

Economy of Austria during the Renaissance

In peaceful periods, trade flourished with neighboring principalities and even with distant Russia. Goods were transported to Hungary, the Czech Republic and Germany along the Danube; in terms of volume, this trade was comparable to trade along the great Rhine route. Trade developed with Venice and other northern Italian cities. Roads were improved, making it easier to transport goods.

Germany served as a profitable market for Austrian wines and grains, Hungary bought textiles. Iron household products were exported to Hungary. In turn, Austria bought Hungarian livestock and minerals. In the Salzkammergut (Lower Austrian Eastern Alps) a large amount of table salt was mined. Domestic needs for most products, except for clothing, were provided by domestic manufacturers. Craftsmen of the same specialty, united in a guild, often settled in certain urban areas, as evidenced by the names of streets in the old corners of Vienna. Wealthy members of the guilds not only controlled the affairs of their industry, but also participated in the management of the city.

Political successes of the Habsburgs

Friedrich III. With the election of Duke Albrecht V as German king in 1438 (under the name of Albrecht II), the prestige of the Habsburgs reached its apogee. By marrying the heiress to the royal throne of Bohemia and Hungary, Albrecht increased the possessions of the dynasty. However, his power in Bohemia remained nominal and soon both crowns were lost to the Habsburgs. The duke died on the way to the place of the battle with the Turks, and during the reign of his son Vladislav, the possessions of the Habsburgs were significantly reduced. After the death of Vladislav, the connection with the Czech Republic and Hungary was completely severed, and Austria itself was divided among the heirs.

In 1452, Albrecht V's uncle Frederick V (1415–1493) was crowned Holy Roman Emperor under the name Frederick III. In 1453 he became Archduke of Austria, and from that time until the formal liquidation of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806 (not counting a short period in the 18th century), the Habsburgs retained the imperial crown.

Despite the endless wars, as well as the rebellions of the nobles and residents of Vienna, Frederick III managed to expand his possessions by annexing part of Istria and the port of Rijeka (1471). Frederick believed that the Habsburg dynasty was destined to conquer the whole world. His motto was the formula "AEIOU" ( Alles Erdreich ist Oesterreich untertan, "The whole land is subject to Austria"). He inscribed this abbreviation on books and ordered it to be carved on public buildings. Frederick married his son and heir Maximilian (1459–1519) to Mary of Burgundy. As a dowry, the Habsburgs got the Netherlands and lands in what is now France. During this period, the rivalry between the Austrian Habsburgs and the French kingdom began, which continued until the 18th century.

Maximilian I (king in 1486, emperor in 1508), sometimes considered the second collector of the Habsburg possessions, acquired, in addition to possessions in Burgundy, the regions of Horoitzia and Gradisca d'Isonzo and small territories in the southern parts of modern Austria. He made an agreement with the Czech-Hungarian king to transfer the Czech-Hungarian crown to Maximilian in the event that Vladislav II died without a male heir.

Thanks to skillful alliances, successful inheritances and advantageous marriages, the Habsburg family achieved impressive power. Maximilian found excellent matches for his son Philip and his grandson Ferdinand. The first married Juan, the heiress of Spain with its vast empire. The dominions of their son, Emperor Charles V, surpassed those of any other European monarch before or after him.

Maximilian arranged for Ferdinand to marry the heiress of Vladislav, King of Bohemia and Hungary. His marriage policy was motivated by dynastic ambitions, but also by a desire to turn Danubian Europe into a cohesive Christian bulwark against Islam. However, the apathy of the people in the face of the Muslim threat made this task difficult.

Along with minor reforms in administration, Maximilian encouraged innovations in the military field, which foreshadowed the creation of a regular standing army in place of the military aristocracy of warrior knights.

Expensive marriage contracts, financial turmoil and military spending emptied the state treasury, and Maximilian resorted to large loans, mainly from the wealthy Fugger magnates of Augsburg. In return, they received mining concessions in Tyrol and other areas. Funds were taken from the same source to bribe the votes of the electors of the Holy Roman Emperor.

Maximilian was a typical Renaissance sovereign. He patronized literature and education, supported scholars and artists such as Konrad Peutinger, a humanist from Augsburg and a specialist in Roman antiquities, and the German artist Albrecht Dürer, who, in particular, illustrated books written by the emperor. Other Habsburg rulers and the aristocracy encouraged the fine arts and amassed rich collections of paintings and sculptures that later became the pride of Austria.

In 1519, Maximilian's grandson Charles was elected king, and in 1530 became Holy Roman Emperor under the name of Charles V. Charles ruled the empire, Austria, Bohemia, the Netherlands, Spain and the Spanish overseas possessions. In 1521 he made his brother, Archduke Ferdinand, ruler of the Danube lands of the Habsburgs, which included Austria proper, Styria, Carinthia, Carniola and Tyrol.

Accession of the Czech Republic and Hungary

In 1526 the troops of Suleiman the Magnificent invaded Hungary. Civil strife within the ruling class of the country facilitated the victory of the Turks, and on August 29 the flower of the Hungarian cavalry was destroyed on the Mohacs field, and the capital Buda capitulated. The young king Louis II, who fled after the defeat at Mohacs, died. After his death, the Czech Republic (with Moravia and Silesia) and Western Hungary went to the Habsburgs.

Until then, the inhabitants of the Habsburg dominions spoke almost exclusively German, except for the population of small Slavic enclaves. However, after the accession of Hungary and the Czech Republic, the Danube State became a very heterogeneous state in terms of population. This happened just at the time when mono-national states were taking shape in the west of Europe.

The Czech Republic and Hungary had their own brilliant past, their own national saints and heroes, traditions and languages. Each of these countries also had its own national estate and provincial diets, which were dominated by wealthy magnates and the clergy, but there were much fewer nobles and townspeople. Royal power was more nominal than real. The Habsburg Empire included many peoples - Hungarians, Slovaks, Czechs, Serbs, Germans, Ukrainians and Romanians.

The court in Vienna undertook a series of measures to integrate Bohemia and Hungary into the Habsburg ancestral domains. The central government departments were reorganized to meet the needs of an expanding power. A prominent role began to be played by the palace office and the secret council, which advised the emperor mainly on issues of international politics and legislation. The first steps were taken to replace the tradition of electing monarchs in both countries with Habsburg hereditary law.

Turkish invasion

Only the threat of Turkish conquest helped to rally Austria, Hungary and the Czech Republic. The 200,000-strong army of Suleiman advanced along the wide valley of the Danube and in 1529 approached the walls of Vienna. A month later, the garrison and the inhabitants of Vienna forced the Turks to lift the siege and retreat to Hungary. But the wars between the Austrian and Ottoman empires continued intermittently for two generations; and almost two centuries passed until the armies of the Habsburgs completely expelled the Turks from historical Hungary.

The Rise and Fall of Protestantism

The area of residence of the Hungarians became the center for the spread of reformed Christianity on the Danube. Many landlords and peasants in Hungary adopted Calvinism and Lutheranism. Luther's teachings attracted many German-speaking townspeople; in Transylvania, the Unitarian movement aroused wide sympathy. In the eastern part of the Hungarian lands proper, Calvinism prevailed, and Lutheranism became widespread among part of the Slovaks and Germans. In that part of Hungary which came under Habsburg control, Protestantism ran into considerable resistance from the Catholics. The court in Vienna, which highly valued the importance of Catholicism in maintaining the absolute power of the king, proclaimed it the official religion of Hungary. Protestants were required to pay money for the maintenance of religious Catholic institutions and for a long time were not allowed to hold public office.

The Reformation spread surprisingly quickly in Austria itself. The newly invented printing allowed both opposing religious camps to publish and distribute books and pamphlets. Princes and priests often fought for power under religious banners. A large number of believers in Austria left the Catholic Church; the ideas of the Reformation were proclaimed in the Cathedral of St. Stephen in Vienna and even in the family chapel of the ruling dynasty. Anabaptist groups (such as the Mennonites) then spread to Tyrol and Moravia. By the middle of the XVI century. the clear majority of the Austrian population seemed to have embraced Protestantism in one form or another.

However, there were three powerful factors that not only restrained the spread of the Reformation, but also contributed to the return of a large part of the neophytes to the bosom of the Roman Catholic Church: the internal church reform proclaimed by the Council of Trent; the Society of Jesus (Jesuit order), whose members, as confessors, teachers and preachers, focused their activities on converting the families of large landowners to this faith, correctly calculating that their peasants would then follow the faith of their masters; and physical coercion carried out by the Viennese court. The conflicts culminated in the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648), which began in Bohemia, where Protestantism was deeply rooted.

Between 1606 and 1609, Rudolf II guaranteed freedom of religion for Czech Protestants through a series of agreements. But when Ferdinand II (reigned 1619–1637) became emperor, Protestants in Bohemia felt their religious and civil rights threatened. The zealous Catholic and authoritarian ruler Ferdinand II, a prominent representative of the Counter-Reformation, ordered the suppression of Protestantism in Austria itself

Thirty Years' War

In 1619, the Czech Diet refused to recognize Ferdinand as emperor and elected Elector Frederick V, Count Palatine of the Rhine, as king. This demarche led to the beginning of the Thirty Years' War. The rebels, who disagreed on all the most important issues, were bound only by hatred of the Habsburgs. With the help of mercenaries from Germany, the Habsburg army utterly defeated the Czech rebels in 1620 at the Battle of Bela Hora near Prague.

The Czech crown was once and for all assigned to the house of Habsburg, the Sejm was dispersed, and Catholicism was declared the only legitimate faith.

The estates of Czech Protestant aristocrats, which occupied almost half of the territory of the Czech Republic, were divided among the younger sons of the Catholic nobility of Europe, mostly of German origin. Until the collapse of the Habsburg Monarchy in 1918, the Czech aristocracy spoke predominantly German and was loyal to the ruling dynasty.

During the Thirty Years' War, the population of the Habsburg Empire suffered huge losses. The Peace of Westphalia (1648) put an end to the massacre, according to which the Holy Roman Empire, which included Germany and Italy, actually ceased to exist, and many princes who owned its lands were able to fulfill their old dream of independence from the power of the emperor. However, the Habsburgs still retained the imperial crown and influence over German state affairs.

Victory over the Turks

In the second half of the XVII century. Ottoman armies resumed the onslaught on Europe. The Austrians fought the Turks for control of the lower reaches of the Danube and Sava rivers. In 1683, a huge Turkish army, taking advantage of an uprising in Hungary, again besieged Vienna for two months, and again caused great damage to its suburbs. The city overflowed with refugees, artillery shelling caused damage to the Cathedral of St. Stephen and other architectural monuments.

The besieged city was saved by the Polish-German army under the command of the Polish king Jan Sobieski. On September 12, 1683, after a fierce skirmish, the Turks withdrew and never returned to the walls of Vienna.

From that moment on, the Turks began to gradually lose their positions, and the Habsburgs derived more and more new benefits from their victories. When, in 1687, most of Hungary, with Buda as its capital, was liberated from Turkish rule, the Hungarian Diet, in gratitude, recognized the hereditary right of the Habsburg male line to the Hungarian crown. However, at the same time, it was stipulated that before accession to the throne, the new king had to confirm all the "traditions, privileges and prerogatives" of the Hungarian nation.

The war against the Turks continued. Austrian troops recaptured almost all of Hungary, Croatia, Transylvania and most of Slovenia, which was officially secured by the Peace of Karlowitz (1699). Then the Habsburgs turned their eyes to the Balkans, and in 1717 the Austrian commander Prince Eugene of Savoy captured Belgrade and invaded Serbia. The Sultan was forced to cede to the Habsburgs a small Serbian region around Belgrade and a number of other small territories. After 20 years, the Balkan territory was again captured by the Turks; The Danube and the Sava became the border between the two great powers.

Hungary, which was under the rule of Vienna, was devastated, its population decreased. Vast tracts of land were given to nobles loyal to the Habsburgs. Hungarian peasants moved to free lands, and foreign settlers invited by the crown - Serbs, Romanians and, above all, German Catholics - settled in the southern regions of the country. It is estimated that in 1720 Hungarians made up less than 45% of the population of Hungary, and in the 18th century. their share continued to decline. Transylvania retained a special political status under the administration from Vienna.

Although the Hungarian constitutional privileges and local government were not affected, and the tax breaks of the aristocracy were confirmed, the Habsburg court was able to impose its will on the Hungarian ruling elite. The aristocracy, whose landholdings grew with their allegiance to the crown, remained loyal to the Habsburgs.

During periods of rebellion and strife in the 16th and 17th centuries. more than once it seemed that the multinational state of the Habsburgs was on the verge of imminent collapse. Nevertheless, the Viennese court continued to encourage the development of education and the arts. Important milestones in intellectual life were the founding of universities in Graz (1585), Salzburg (1623), Budapest (1635) and Innsbruck (1677).

Military successes

In Austria, a regular army was created, equipped with firearms. Although gunpowder was first used in war in the 14th century, it took 300 years for guns and artillery to become truly formidable weapons. Artillery pieces made of iron or bronze were so heavy that at least 10 horses or 40 oxen had to be harnessed to move them. To protect against bullets, armor was needed, burdensome for both people and horses. Fortress walls were made thicker in order to withstand artillery fire. The disregard for the infantry gradually disappeared, and the cavalry, although reduced in numbers, lost little of its former prestige. Military operations largely began to be reduced to the siege of fortified cities, which required a lot of manpower and equipment.

Prince Eugene of Savoy rebuilt the armed forces along the lines of the army of France, where he received his military education. Food was improved, troops were housed in barracks, veterans were given land reclaimed from the Turks. However, the reform was soon obstructed by aristocrats from the Austrian military command. The changes were not deep enough to allow Austria to win against Prussia in the 18th century. For generations, however, the Habsburgs' armed forces and bureaucracy provided the stronghold they needed to maintain the integrity of the multinational state.

Economic situation

The basis of the Austrian economy remained agriculture, but at the same time there was an increase in manufacturing production and finance capital. In the XVI century. the country's industry several times experienced a crisis due to inflation caused by the import of precious metals into Europe from America. At this time, the crown no longer had to turn to usurers for financial assistance, now the state loan became the source of funds. In sufficient quantities for the market, iron was mined in Styria and silver in Tyrol; to a lesser extent, coal in Silesia.

architectural masterpieces

After the feeling of the Turkish threat disappeared, intensive construction began in the cities of the Habsburg Empire. Masters from Italy trained local designers and builders of churches and palaces. Baroque buildings were erected in Prague, Salzburg and especially in Vienna - smart, elegant, with rich exterior and interior decoration. Luxuriously decorated facades, wide staircases and luxurious gardens became characteristic features of the city residences of the Austrian aristocracy. Among them stood out the magnificent Belvedere Palace with a park built by Prince Eugene of Savoy.

The ancient seat of the court in Vienna, the Hofburg, was enlarged and decorated. The chancellery of the court, the huge Karlskirche church, which took 20 years to build, and the imperial summer palace and park in Schönbrunn are just the most striking buildings in a city that shone with its architectural splendor. Churches and monasteries damaged or destroyed during the war were restored throughout the monarchy. The Benedictine monastery in Melk, perched on a cliff above the Danube, is a typical baroque example in rural Austria and a symbol of the triumph of the Counter-Reformation.

Rise of Vienna