Austria Habsburg dynasty. A brief history of the Habsburg state. Unrest among national minorities

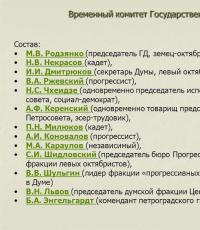

Coat of arms of the Counts of Habsburg

In a golden field is a scarlet lion, armed and crowned with azure.

Habsburgs

The Habsburgs were one of the most powerful royal dynasties in Europe during the Middle Ages and Modern times.

The ancestor of the Habsburgs was Count Guntram the Rich, whose domains lay in Northern Switzerland and Alsace. His grandson Radboth built the Habsburg castle near the Are River, which gave the name to the dynasty. The name of the castle, according to legend, was originally Habichtsburg ( Habichtsburg), "Hawk Castle", in honor of the hawk that landed on the newly built walls of the fortress. According to another version, the name comes from Old German hab- ford: the fortress was supposed to guard the crossing of the Are River. (The castle was lost to the Habsburgs in the 15th century; the territory in which it was located became part of the Swiss Confederation). Radbot's descendants annexed a number of possessions in Alsace (Sundgau) and most of northern Switzerland to their possessions, becoming by the middle of the 13th century one of the largest feudal families in the southwestern outskirts of Germany. The first hereditary title of the family was the title of Count of Habsburg.

Albrecht IV and Rudolf III (descendants of Radboth in the sixth generation) divided the family domains: the first received the western part, including Aargau and Sundgau, and the second lands in eastern Switzerland. The descendants of Albrecht IV were considered the main line, and the heirs of Rudolf III began to be called the title Count of Habsburg-Laufenburg. Representatives of the Laufenburg line did not play a significant role in German politics and remained, like many other German aristocratic families, a regional feudal house. Their possessions included the eastern part of Aargau, Thurgau, Klettgau, Kyburg and a number of fiefs in Burgundy. This line ended in 1460.

The entry of the Habsburgs into the European arena is associated with the name of the son of Count Albrecht IV (1218-1291). He annexed the vast principality of Kyburg to the Habsburg possessions, and in 1273 he was elected king of Germany by the German princes under the name. Having become king, he tried to strengthen central power in the Holy Roman Empire, but his main success was the victory over the Czech king in 1278, as a result of which the duchies of Austria and Styria came under control.

In 1282, the king transferred these possessions to his children and. Thus, the Habsburgs became rulers of a vast and rich Danube state, which quickly eclipsed their ancestral domains in Switzerland, Swabia and Alsace.

The new monarch was unable to get along with the Protestants, whose rebellion resulted in the Thirty Years' War, which radically changed the balance of power in Europe. The fighting ended with the Peace of Westphalia (1648), which strengthened the position and hurt the interests of the Habsburgs (in particular, they lost all their possessions in Alsace).

In 1659, the French king dealt a new blow to the prestige of the Habsburgs - the Peace of the Pyrenees left the western part of the Spanish Netherlands, including the County of Artois, for the French. By this time it became obvious that they had won the confrontation with the Habsburgs for supremacy in Europe.

In the 19th century, the House of Habsburg-Lorraine split into the following branches:

- Imperial- all the descendants of the first Austrian emperor belong to it. Its representatives returned to Russia after World War II, abandoning the noble prefix "von". This branch is now headed by Charles of Habsburg-Lorraine, grandson of the last Austrian Emperor.

- Tuscan- descendants of the brother who received Tuscany in exchange for the lost Lorraine. After the Risorgimento, the Tuscan Habsburgs returned to Vienna. Now it is the most numerous of the Habsburg branches.

- Teshenskaya- descendants of Karl Ludwig, younger brother. Now this branch is represented by several lines.

- Hungarian- she is represented by her childless brother, Joseph, Palatine of Hungary.

- Modena(Austrian Este) - descendants of Ferdinand Charles, the sixth son of the Emperor. This branch was stopped in 1876. In 1875, the title of Duke of Este was transferred to Franz Ferdinand, and after his assassination in 1914 in Sarajevo - to Robert, the second son, and on his mother's side, a descendant of the original Modena Estes. The current head of this line, Karl Otto Lorenz, is married to the Belgian Princess Astrid and lives in Belgium.

In addition to the five main ones, there are two morganatic branches of the Habsburgs:

- Hohenbergs- descendants of the unequal marriage of Archduke Franz Ferdinand with Sophia Chotek. The Hohenbergs, although they are the eldest among the living Habsburgs, do not claim primacy in the dynasty. This branch is now headed by Georg Hohenberg, Knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece, former Austrian ambassador to the Vatican.

- Merans- descendants from the marriage of Johann Baptist, the youngest son, with the daughter of the postmaster, Anna Plöchl.

Representatives of the Habsburg dynasty

King of Germany, Duke of Austria and Styria

, Duke of Austria, Styria and Carinthia

, King of Germany, King of Hungary (Albert), King of Bohemia (Albrecht), Duke of Austria (Albrecht V)

, Duke of Austria, Styria and Carinthia, Count of Tyrol

, Duke of Austria

, Archduke of Austria

, Duke of Western Austria, Styria, Carinthia and Carniola, Count of Tyrol

, Duke of Swabia

, Holy Roman Emperor, King of Germany, Bohemia, Hungary, Archduke of Austria

, Emperor of Austria, King of Bohemia (Charles III), King of Hungary (Charles IV)

, King of Spain

, Holy Roman Emperor, King of Germany, King of Spain (Aragon, Leon, Castile, Valencia), Count of Barcelona (Charles I), King of Sicily (Charles II), Duke of Brabant (Charles), Count of Holland (Charles II), Archduke of Austria (Charles I)

The Habsburg dynasty has been known since the 13th century, when its representatives ruled Austria. And from the middle of the 15th century until the beginning of the 19th century, they completely retained the title of Emperors of the Holy Roman Empire, being the most powerful monarchs of the continent.

Habsburg history

The founder of the family lived in the 10th century. Almost no information has been preserved about him today. It is known that his descendant, Count Rudolf, acquired lands in Austria already in the middle of the 13th century. Actually, southern Swabia became their cradle, where the early representatives of the dynasty had a family castle. The name of the castle - Habischtsburg (from German - “hawk castle”) gave the name to the dynasty. In 1273, Rudolf was elected king of the Germans and emperor. He conquered Austria and Styria from the Bohemian king Přemysl Otakar, and his sons Rudolf and Albrecht became the first Habsburgs to rule in Austria. In 1298, Albrecht inherited the title of Emperor and German King from his father. And subsequently his son was elected to this throne. At the same time, throughout the 14th century, the title of Holy Roman Emperor and King of the Germans was still elective between German princes, and it did not always go to representatives of the dynasty. Only in 1438, when Albrecht II became emperor, did the Habsburgs finally appropriate this title to themselves. There was only one exception later, when the Elector of Bavaria achieved royal rank by force in the middle of the 18th century.

Rise of the Dynasty

From this period, the Habsburg dynasty gained increasing power, reaching brilliant heights. Their successes were laid down by the successful policies of I, who ruled at the end of the 15th - beginning of the 16th centuries. Actually, his main successes were successful marriages: his own, which brought him the Netherlands, and his son Philip, as a result of which the Habsburg dynasty took possession of Spain. About the grandson of Maximilian, they said that the Sun never sets on his domain - his power was so widespread. He owned Germany, the Netherlands, parts of Spain and Italy, as well as some possessions in the New World. The Habsburg dynasty was at the height of its power.

However, even during the life of this monarch, the gigantic state was divided into parts. And after his death it completely disintegrated, after which the representatives of the dynasty divided their possessions among themselves. Ferdinand I got Austria and Germany, Philip II got Spain and Italy. Subsequently, the Habsburgs, whose dynasty was divided into two branches, were no longer a single whole. In some periods, relatives even openly opposed each other. As was the case, for example, during

Europe. The victory of the reformers in it greatly damaged the power of both branches. Thus, the Holy Emperor never again had his former influence, which was associated with his rise in Europe. And the Spanish Habsburgs completely lost their throne, losing it to the Bourbons.

In the middle of the 18th century, the Austrian rulers Joseph II and Leopold II for some time managed to once again raise the prestige and power of the dynasty. This second heyday, when the Habsburgs once again became influential in Europe, lasted about a century. However, after the revolution of 1848, the dynasty loses its monopoly on power even in its own empire. Austria turns into a dual monarchy - Austria-Hungary. The further - already irreversible - process of collapse was delayed only thanks to the charisma and wisdom of the reign of Franz Joseph, who became the last real ruler of the state. The Habsburg dynasty (photo on the right), after the defeat in the First World War, was expelled from the country in its entirety, and a number of national independent states arose from the ruins of the empire in 1919.

Emperors who made elective office hereditary.

The Habsburgs were a dynasty that ruled the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation (until 1806), Spain (1516-1700), the Austrian Empire (formally from 1804), and Austria-Hungary (1867-1918).

The Habsburgs were one of the richest and most influential families in Europe. A distinctive feature of the Habsburgs' appearance was their prominent, slightly drooping lower lip.

Charles II of Habsburg

The family castle of an ancient family, built at the beginning of the 11th century, was called Habsburg (from Habichtsburg - Hawk's Nest). The dynasty received its name from him.

Castle Hawk's Nest, Switzerland

The Habsburg family castle - Schönbrunn - is located near Vienna. It is a modernized copy of Louis XIV's Versailles and is where much of the Habsburg family and political life took place.

Habsburg Summer Castle - Schönbrunn, Austria

And the main residence of the Habsburgs in Vienna was the Hofburg (Burg) palace complex.

Habsburg Winter Castle - Hofburg, Austria

In 1247, Count Rudolf of Habsburg was elected king of Germany, marking the beginning of a royal dynasty. Rudolf I annexed the lands of Bohemia and Austria to his possessions, which became the center of the dominion. The first emperor from the ruling Habsburg dynasty was Rudolf I (1218-1291), German king since 1273. During his reign in 1273-1291, he took Austria, Styria, Carinthia and Carniola from the Czech Republic, which became the main core of the Habsburg possessions.

Rudolf I of Habsburg (1273-1291)

Rudolf I was succeeded by his eldest son Albrecht I, who was elected king in 1298.

Albrecht I of Habsburg

Then, for almost a hundred years, representatives of other families occupied the German throne, until Albrecht II was elected king in 1438. Since then, representatives of the Habsburg dynasty have been constantly (with the exception of a single break in 1742-1745) elected kings of Germany and emperors of the Holy Roman Empire. The only attempt in 1742 to elect another candidate, the Bavarian Wittelsbach, led to civil war.

Albrecht II of Habsburg

The Habsburgs received the imperial throne at a time when only a very strong dynasty could hold onto it. Through the efforts of the Habsburgs - Frederick III, his son Maximilian I and great-grandson Charles V - the highest prestige of the imperial title was restored, and the idea of empire itself received new content.

Frederick III of Habsburg

Maximilian I (emperor from 1493 to 1519) annexed the Netherlands to the Austrian possessions. In 1477, by marrying Mary of Burgundy, he added to the Habsburg domains Franche-Comté, a historical province in eastern France. He married his son Charles to the daughter of the Spanish king, and thanks to the successful marriage of his grandson, he received the rights to the Czech throne.

Emperor Maximilian I. Portrait by Albrecht Durer (1519)

Bernhard Striegel. Portrait of Emperor Maximilian I and his family

Bernaert van Orley. Young Charles V, son of Maximilian I. Louvre

Maximilian I. Portrait by Rubens, 1618

After the death of Maximilian I, three powerful kings claimed the imperial crown of the Holy Roman Empire - Charles V of Spain himself, Francis I of France and Henry VIII of England. But Henry VIII quickly abandoned the crown, and Charles and Francis continued this struggle with each other almost all their lives.

In the struggle for power, Charles used the silver of his colonies in Mexico and Peru and money borrowed from the richest bankers of that time to bribe the electors, giving them Spanish mines in return. And the electors elected the heir of the Habsburgs to the imperial throne. Everyone hoped that he would be able to withstand the onslaught of the Turks and protect Europe from their invasion with the help of the fleet. The new emperor was forced to accept conditions according to which only Germans could hold public positions in the empire, the German language was to be used on an equal basis with Latin, and all meetings of government officials were to be held only with the participation of the electors.

Charles V of Habsburg

Titian, Portrait of Charles V with his dog, 1532-33. Oil on canvas, Prado Museum, Madrid

Titian, Portrait of Charles V in an Armchair, 1548

Titian, Emperor Charles V at the Battle of Mühlberg

So Charles V became the ruler of a huge empire, which included Austria, Germany, the Netherlands, Southern Italy, Sicily, Sardinia, Spain and the Spanish colonies in America - Mexico and Peru. The “world power” under his rule was so great that “the sun never set” on it.

Even his military victories did not bring the desired success to Charles V. He declared the goal of his policy to be the creation of a “worldwide Christian monarchy.” But internal strife between Catholics and Protestants destroyed the empire, the greatness and unity of which he dreamed of. During his reign, the Peasants' War of 1525 broke out in Germany, the Reformation took place, and the Comuneros uprising took place in Spain in 1520-1522.

The collapse of the political program forced the emperor to eventually sign the Religious Peace of Augsburg, and now each elector within his principality could adhere to the faith that he liked best - Catholic or Protestant, that is, the principle “whose power, whose faith” was proclaimed. In 1556, he sent a message to the electors renouncing the imperial crown, which he ceded to his brother Ferdinand I (1556-64), who had been elected king of Rome back in 1531. In the same year, Charles V abdicated the Spanish throne in favor of his son Philip II and retired to a monastery, where he died two years later.

Emperor Ferdinand I of Habsburg in a portrait by Boxberger

Philip II of Habsburg in ceremonial armor

Austrian branch of the Habsburgs

Castile in 1520-1522 against absolutism. At the Battle of Villalar (1521), the rebels were defeated and ceased resistance in 1522. Government repression continued until 1526. Ferdinand I managed to secure for the Habsburgs the right of ownership of the lands of the crown of St. Wenceslas and St. Stephen, which significantly increased the possessions and prestige of the Habsburgs. He was tolerant of both Catholics and Protestants, as a result of which the great empire actually disintegrated into separate states.

Already during his lifetime, Ferdinand I ensured continuity by holding the election of the Roman king in 1562, which was won by his son Maximilian II. He was an educated man with gallant manners and deep knowledge of modern culture and art.

Maximilian II of Habsburg

Giuseppe Arcimboldo. Portrait of Maximilian II with his family, c. 1563

Maximilian II evokes very contradictory assessments by historians: he is both a “mysterious emperor,” and a “tolerant emperor,” and “a representative of humanistic Christianity of the Erasmus tradition,” but recently he is most often called the “emperor of the religious world.” Maximilian II of Habsburg continued the policies of his father, who sought to find compromises with opposition-minded subjects of the empire. This position provided the emperor with extraordinary popularity in the empire, which contributed to the unhindered election of his son, Rudolf II, as the Roman king and then emperor.

Rudolf II of Habsburg

Rudolf II of Habsburg

Rudolf II was brought up at the Spanish court, had a deep mind, strong will and intuition, was far-sighted and prudent, but for all that he was timid and prone to depression. In 1578 and 1581 he suffered serious illnesses, after which he stopped appearing at hunts, tournaments and festivals. Over time, suspicion developed in him, and he began to fear witchcraft and poisoning, sometimes he thought about suicide, and in recent years he sought oblivion in drunkenness.

Historians believe that the cause of his mental illness was his bachelor life, but this is not entirely true: the emperor had a family, but not one consecrated by marriage. He had a long relationship with the daughter of the antiquarian Jacopo de la Strada, Maria, and they had six children.

The emperor's favorite son, Don Julius Caesar of Austria, was mentally ill, committed a brutal murder and died in custody.

Rudolf II of Habsburg was an extremely versatile person: he loved Latin poetry, history, devoted a lot of time to mathematics, physics, astronomy, and was interested in occult sciences (there is a legend that Rudolf had contacts with Rabbi Lev, who allegedly created the “Golem”, an artificial man) . During his reign, mineralogy, metallurgy, zoology, botany and geography received significant development.

Rudolf II was the largest collector in Europe. His passion was the works of Durer, Pieter Bruegel the Elder. He was also known as a watch collector. His encouragement of jewelry culminated in the creation of the magnificent Imperial Crown, the symbol of the Austrian Empire.

Personal crown of Rudolf II, later crown of the Austrian Empire

He proved himself to be a talented commander (in the war with the Turks), but was unable to take advantage of the fruits of this victory; the war became protracted. This sparked a rebellion in 1604, and in 1608 the emperor abdicated in favor of his brother Matthias. It must be said that Rudolf II resisted this turn of affairs for a long time and extended the transfer of powers to the heir for several years. This situation tired both the heir and the population. Therefore, everyone breathed a sigh of relief when Rudolf II died of dropsy on January 20, 1612.

Matthias Habsburg

Matthias received only the appearance of power and influence. The finances in the state were completely upset, the foreign policy situation was steadily leading to a big war, domestic politics threatened another uprising, and the victory of the irreconcilable Catholic party, at the origins of which Matthias stood, actually led to his overthrow.

This sad inheritance went to Ferdinand of Central Austria, who was elected Roman Emperor in 1619. He was a friendly and generous gentleman to his subjects and a very happy husband (in both of his marriages).

Ferdinand II of Habsburg

Ferdinand II loved music and adored hunting, but work came first for him. He was deeply religious. During his reign, he successfully overcame a number of difficult crises, he managed to unite the politically and religiously divided possessions of the Habsburgs and began a similar unification in the empire, which was to be completed by his son, Emperor Ferdinand III.

Ferdinand III of Habsburg

The most important political event of the reign of Ferdinand III is the Peace of Westphalia, with the conclusion of which the Thirty Years' War ended, which began as an uprising against Matthias, continued under Ferdinand II and was stopped by Ferdinand III. By the time peace was signed, 4/5 of all war resources were in the hands of the emperor’s opponents, and the last parts of the imperial army capable of maneuvering were defeated. In this situation, Ferdinand III proved himself to be a strong politician, capable of making decisions independently and consistently implementing them. Despite all the defeats, the emperor perceived the Peace of Westphalia as a success that prevented even more serious consequences. But the treaty, signed under pressure from the electors, which brought peace to the empire, simultaneously undermined the authority of the emperor.

The prestige of the emperor's power had to be restored by Leopold I, who was elected in 1658 and ruled for 47 years after that. He managed to successfully play the role of the emperor as a defender of law and law, restoring the authority of the emperor step by step. He worked long and hard, traveling outside the empire only when necessary, and made sure that strong personalities did not occupy a dominant position for a long time.

Leopold I of Habsburg

The alliance with the Netherlands concluded in 1673 allowed Leopold I to strengthen the foundations for Austria's future position as a great European power and achieve its recognition among the electors - subjects of the empire. Austria again became the center around which the empire was defined.

Under Leopold, Germany experienced a revival of Austrian and Habsburg hegemony in the empire, the birth of the "Viennese Imperial Baroque". The emperor himself was known as a composer.

Leopold I of Hasburg was succeeded by Emperor Joseph I of Habsburg. The beginning of his reign was brilliant, and a great future was predicted for the emperor, but his undertakings were not completed. Soon after his election, it became clear that he preferred hunting and amorous adventures to serious work. His affairs with court ladies and chambermaids caused a lot of trouble for his respectable parents. Even the attempt to marry Joseph was unsuccessful, because the wife could not find the strength to tie her irrepressible hubby.

Joseph I of Habsburg

Joseph died of smallpox in 1711, remaining in history as a symbol of hope that was not destined to come true.

Charles VI became the Roman emperor, who had previously tried his hand as King Charles III of Spain, but was not recognized by the Spaniards and was not supported by other rulers. He managed to maintain peace in the empire without losing the authority of the emperor.

Charles VI of Habsburg, last of the Habsburgs in the male line

However, he was unable to ensure the continuity of the dynasty, since there was no son among his children (he died in infancy). Therefore, Charles took care to regulate the order of inheritance. A document known as the Pragmatic Sanction was adopted, according to which, after the complete extinction of the ruling branch, the right of succession was first given to the daughters of his brother, and then to his sisters. This document contributed greatly to the rise of his daughter Maria Theresa, who ruled the empire first with her husband, Franz I, and then with her son, Joseph II.

Maria Theresa at age 11

But in history, not everything was so smooth: with the death of Charles VI, the male line of the Habsburgs was interrupted, and Charles VII from the Wittelsbach dynasty was elected emperor, which forced the Habsburgs to remember that the empire is an elective monarchy and its governance is not associated with a single dynasty.

Portrait of Maria Theresa

Maria Theresa made attempts to return the crown to her family, which she succeeded after the death of Charles VII - her husband, Franz I, became emperor. However, in fairness, it should be noted that Franz was not an independent politician, because all affairs in the empire were taken into his hands tireless wife. Maria Theresa and Franz were happily married (despite Franz's numerous infidelities, which his wife preferred not to notice), and God blessed them with numerous offspring: 16 children. Surprisingly, but true: the empress even gave birth as if casually: she worked with documents until the doctors sent her to the maternity room, and immediately after giving birth she continued to sign documents and only after that could she afford to rest. She entrusted the care of raising her children to trusted persons, strictly supervising them. Her interest in the destinies of her children truly manifested itself only when the time came to think about the arrangement of their marriages. And here Maria Theresa showed truly remarkable abilities. She arranged the weddings of her daughters: Maria Caroline married the King of Naples, Maria Amelia married the Infante of Parma, and Marie Antoinette, married to the Dauphin of France Louis (XVI), became the last queen of France.

Maria Theresa, who pushed her husband into the shadow of big politics, did the same with her son, which is why their relationship was always tense. As a result of these skirmishes, Joseph chose to travel.

Francis I Stephen, Francis I of Lorraine

During his trips he visited Switzerland, France, and Russia. Traveling not only expanded the circle of his personal acquaintances, but also increased his popularity among his subjects.

After the death of Maria Theresa in 1780, Joseph was finally able to carry out the reforms that he had thought about and prepared during his mother’s time. This program was born, carried out and died with him. Joseph was alien to dynastic thinking; he sought to expand the territory and pursue the Austrian great-power policy. This policy turned almost the entire empire against him. Nevertheless, Joseph still managed to achieve some results: in 10 years he changed the face of the empire so much that only his descendants were able to truly appreciate his work.

Joseph II, eldest son of Maria Theresa

It was clear to the new monarch, Leopold II, that the empire would only be saved by concessions and a slow return to the past, but while his goals were clear, he had no clarity in actually achieving them, and, as it turned out later, he also did not have time, because the emperor died 2 years after election.

Leopold II, third son of Franz I and Maria Theresa

Francis II reigned for over 40 years, under him the Austrian Empire was formed, under him the final collapse of the Roman Empire was recorded, under him Chancellor Metternich ruled, after whom an entire era was named. But the emperor himself, in historical light, appears as a shadow bending over state papers, a vague and amorphous shadow, incapable of independent body movements.

Franz II with the scepter and crown of the new Austrian Empire. Portrait by Friedrich von Amerling. 1832. Museum of Art History. Vein

At the beginning of his reign, Francis II was a very active politician: he carried out management reforms, mercilessly changed officials, experimented in politics, and his experiments simply took the breath away of many. It was later that he would become a conservative, suspicious and unsure of himself, unable to make global decisions...

Francis II assumed the title of Hereditary Emperor of Austria in 1804, which was associated with the proclamation of Napoleon as Hereditary Emperor of the French. And by 1806, circumstances were such that the Roman Empire had become a ghost. If in 1803 there were still some remnants of imperial consciousness, now they were not even remembered. Having soberly assessed the situation, Francis II decided to relinquish the crown of the Holy Roman Empire and from that moment devoted himself entirely to strengthening Austria.

In his memoirs, Metternich wrote about this turn of history: “Franz, deprived of the title and the rights that he had before 1806, but incomparably more powerful than then, was now the true emperor of Germany.”

Ferdinand I of Austria "The Good" modestly ranks between his predecessor and his successor Franz Joseph I.

Ferdinand I of Austria "The Good"

Ferdinand I was very popular among the people, as evidenced by numerous anecdotes. He was a supporter of innovations in many areas: from the construction of the railroad to the first long-distance telegraph line. By decision of the emperor, the Military Geographical Institute was created and the Austrian Academy of Sciences was founded.

The emperor was sick with epilepsy, and the disease left its mark on the attitude towards him. He was called “blessed”, “fool”, “stupid”, etc. Despite all these unflattering epithets, Ferdinand I showed various abilities: he knew five languages, played the piano, and was fond of botany. In the matter of government, he also achieved certain successes. Thus, during the revolution of 1848, it was he who realized that Metternich’s system, which had worked successfully for many years, had outlived its usefulness and required replacement. And Ferdinand Joseph had the firmness to refuse the services of the chancellor.

During the difficult days of 1848, the emperor tried to resist circumstances and pressure from others, but he was eventually forced to abdicate, followed by Archduke Franz Karl. Franz Joseph, the son of Franz Karl, who ruled Austria (and then Austria-Hungary) for no less than 68 years, became emperor. The first years the emperor ruled under the influence, if not under the leadership, of his mother, Empress Sophia.

Franz Joseph in 1853. Portrait by Miklós Barabás

Franz Joseph I of Austria

For Franz Joseph I of Austria, the most important things in the world were: dynasty, army and religion. At first, the young emperor zealously took up the matter. Already in 1851, after the defeat of the revolution, the absolutist regime in Austria was restored.

In 1867, Franz Joseph transformed the Austrian Empire into the dual monarchy of Austria-Hungary, in other words, he made a constitutional compromise that retained for the emperor all the advantages of an absolute monarch, but at the same time left all the problems of the state system unresolved.

The policy of coexistence and cooperation between the peoples of Central Europe is the Habsburg tradition. It was a conglomerate of peoples, essentially equal, because everyone, be it a Hungarian or a Bohemian, a Czech or a Bosnian, could occupy any government post. They ruled in the name of the law and did not take into account the national origin of their subjects. For nationalists, Austria was a “prison of nations,” but, oddly enough, the people in this “prison” grew rich and prospered. Thus, the House of Habsburg really assessed the benefits of having a large Jewish community on the territory of Austria and invariably defended the Jews from the attacks of Christian communities - so much so that anti-Semites even nicknamed Franz Joseph the “Jewish Emperor.”

Franz Joseph loved his charming wife, but on occasion he could not resist the temptation to admire the beauty of other women, who usually reciprocated his feelings. He also could not resist gambling, often visiting the Monte Carlo casino. Like all Habsburgs, the emperor under no circumstances misses the hunt, which has a pacifying effect on him.

The Habsburg monarchy was swept away by the whirlwind of revolution in October 1918. The last representative of this dynasty, Charles I of Austria, was overthrown after being in power for only about two years, and all the Habsburgs were expelled from the country.

Charles I of Austria

The last representative of the Habsburg dynasty in Austria - Charles I of Austria and his wife

There was an ancient legend in the Habsburg family: the proud family would begin with Rudolf and end with Rudolf. The prediction almost came true, for the dynasty fell after the death of Crown Prince Rudolf, the only son of Franz Joseph I of Austria. And if the dynasty remained on the throne after his death for another 27 years, then for a prediction made many centuries ago, this is a minor error.

THE HABSBURGS. Part 1. Austrian branch of the Habsburgs

Emperors who made elective office hereditary.

The Habsburgs were a dynasty that ruled the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation (until 1806), Spain (1516-1700), the Austrian Empire (formally from 1804), and Austria-Hungary (1867-1918).

The Habsburgs were one of the richest and most influential families in Europe. A distinctive feature of the Habsburgs' appearance was their prominent, slightly drooping lower lip.

Charles II of Habsburg

The family castle of an ancient family, built at the beginning of the 11th century, was called Habsburg (from Habichtsburg - Hawk's Nest). The dynasty received its name from him.

Castle Hawk's Nest, Switzerland

The Habsburg family castle - Schönbrunn - is located near Vienna. It is a modernized copy of Louis XIV's Versailles and is where much of the Habsburg family and political life took place.

Habsburg Summer Castle - Schönbrunn, Austria

And the main residence of the Habsburgs in Vienna was the Hofburg (Burg) palace complex.

Habsburg Winter Castle - Hofburg, Austria

In 1247, Count Rudolf of Habsburg was elected king of Germany, marking the beginning of a royal dynasty. Rudolf I annexed the lands of Bohemia and Austria to his possessions, which became the center of the dominion. The first emperor from the ruling Habsburg dynasty was Rudolf I (1218-1291), German king since 1273. During his reign in 1273-1291, he took Austria, Styria, Carinthia and Carniola from the Czech Republic, which became the main core of the Habsburg possessions.

Rudolf I of Habsburg (1273-1291)

Rudolf I was succeeded by his eldest son Albrecht I, who was elected king in 1298.

Albrecht I of Habsburg

Then, for almost a hundred years, representatives of other families occupied the German throne, until Albrecht II was elected king in 1438. Since then, representatives of the Habsburg dynasty have been constantly (with the exception of a single break in 1742-1745) elected kings of Germany and emperors of the Holy Roman Empire. The only attempt in 1742 to elect another candidate, the Bavarian Wittelsbach, led to civil war.

Albrecht II of Habsburg

The Habsburgs received the imperial throne at a time when only a very strong dynasty could hold onto it. Through the efforts of the Habsburgs - Frederick III, his son Maximilian I and great-grandson Charles V - the highest prestige of the imperial title was restored, and the idea of empire itself received new content.

Frederick III of Habsburg

Maximilian I (emperor from 1493 to 1519) annexed the Netherlands to the Austrian possessions. In 1477, by marrying Mary of Burgundy, he added to the Habsburg domains Franche-Comté, a historical province in eastern France. He married his son Charles to the daughter of the Spanish king, and thanks to the successful marriage of his grandson, he received the rights to the Czech throne.

Emperor Maximilian I. Portrait by Albrecht Durer (1519)

Bernhard Striegel. Portrait of Emperor Maximilian I and his family

Bernaert van Orley. Young Charles V, son of Maximilian I. Louvre

Maximilian I. Portrait by Rubens, 1618

After the death of Maximilian I, three powerful kings claimed the imperial crown of the Holy Roman Empire - Charles V of Spain himself, Francis I of France and Henry VIII of England. But Henry VIII quickly abandoned the crown, and Charles and Francis continued this struggle with each other almost all their lives.

In the struggle for power, Charles used the silver of his colonies in Mexico and Peru and money borrowed from the richest bankers of that time to bribe the electors, giving them Spanish mines in return. And the electors elected the heir of the Habsburgs to the imperial throne. Everyone hoped that he would be able to withstand the onslaught of the Turks and protect Europe from their invasion with the help of the fleet. The new emperor was forced to accept conditions according to which only Germans could hold public positions in the empire, the German language was to be used on an equal basis with Latin, and all meetings of government officials were to be held only with the participation of the electors.

Charles V of Habsburg

Titian, Portrait of Charles V with his dog, 1532-33. Oil on canvas, Prado Museum, Madrid

Titian, Portrait of Charles V in an Armchair, 1548

Titian, Emperor Charles V at the Battle of Mühlberg

So Charles V became the ruler of a huge empire, which included Austria, Germany, the Netherlands, Southern Italy, Sicily, Sardinia, Spain and the Spanish colonies in America - Mexico and Peru. The “world power” under his rule was so great that “the sun never set” on it.

Even his military victories did not bring the desired success to Charles V. He declared the goal of his policy to be the creation of a “worldwide Christian monarchy.” But internal strife between Catholics and Protestants destroyed the empire, the greatness and unity of which he dreamed of. During his reign, the Peasants' War of 1525 broke out in Germany, the Reformation took place, and the Comuneros uprising took place in Spain in 1520-1522.

The collapse of the political program forced the emperor to eventually sign the Religious Peace of Augsburg, and now each elector within his principality could adhere to the faith that he liked best - Catholic or Protestant, that is, the principle “whose power, whose faith” was proclaimed. In 1556, he sent a message to the electors renouncing the imperial crown, which he ceded to his brother Ferdinand I (1556-64), who had been elected king of Rome back in 1531. In the same year, Charles V abdicated the Spanish throne in favor of his son Philip II and retired to a monastery, where he died two years later.

Emperor Ferdinand I of Habsburg in a portrait by Boxberger

Philip II of Habsburg in ceremonial armor

Austrian branch of the Habsburgs

Castile in 1520-1522 against absolutism. At the Battle of Villalar (1521), the rebels were defeated and ceased resistance in 1522. Government repression continued until 1526. Ferdinand I managed to secure for the Habsburgs the right of ownership of the lands of the crown of St. Wenceslas and St. Stephen, which significantly increased the possessions and prestige of the Habsburgs. He was tolerant of both Catholics and Protestants, as a result of which the great empire actually disintegrated into separate states.

Already during his lifetime, Ferdinand I ensured continuity by holding the election of the Roman king in 1562, which was won by his son Maximilian II. He was an educated man with gallant manners and deep knowledge of modern culture and art.

Maximilian II of Habsburg

Giuseppe Arcimboldo. Portrait of Maximilian II with his family, c. 1563

Maximilian II evokes very contradictory assessments by historians: he is both a “mysterious emperor,” and a “tolerant emperor,” and “a representative of humanistic Christianity of the Erasmus tradition,” but recently he is most often called the “emperor of the religious world.” Maximilian II of Habsburg continued the policies of his father, who sought to find compromises with opposition-minded subjects of the empire. This position provided the emperor with extraordinary popularity in the empire, which contributed to the unhindered election of his son, Rudolf II, as the Roman king and then emperor.

Rudolf II of Habsburg

Rudolf II of Habsburg

Rudolf II was brought up at the Spanish court, had a deep mind, strong will and intuition, was far-sighted and prudent, but for all that he was timid and prone to depression. In 1578 and 1581 he suffered serious illnesses, after which he stopped appearing at hunts, tournaments and festivals. Over time, suspicion developed in him, and he began to fear witchcraft and poisoning, sometimes he thought about suicide, and in recent years he sought oblivion in drunkenness.

Historians believe that the cause of his mental illness was his bachelor life, but this is not entirely true: the emperor had a family, but not one consecrated by marriage. He had a long relationship with the daughter of the antiquarian Jacopo de la Strada, Maria, and they had six children.

The emperor's favorite son, Don Julius Caesar of Austria, was mentally ill, committed a brutal murder and died in custody.

Rudolf II of Habsburg was an extremely versatile person: he loved Latin poetry, history, devoted a lot of time to mathematics, physics, astronomy, and was interested in occult sciences (there is a legend that Rudolf had contacts with Rabbi Lev, who allegedly created the “Golem”, an artificial man) . During his reign, mineralogy, metallurgy, zoology, botany and geography received significant development.

Rudolf II was the largest collector in Europe. His passion was the works of Durer, Pieter Bruegel the Elder. He was also known as a watch collector. His encouragement of jewelry culminated in the creation of the magnificent Imperial Crown, the symbol of the Austrian Empire.

Personal crown of Rudolf II, later crown of the Austrian Empire

He proved himself to be a talented commander (in the war with the Turks), but was unable to take advantage of the fruits of this victory; the war became protracted. This sparked a rebellion in 1604, and in 1608 the emperor abdicated in favor of his brother Matthias. It must be said that Rudolf II resisted this turn of affairs for a long time and extended the transfer of powers to the heir for several years. This situation tired both the heir and the population. Therefore, everyone breathed a sigh of relief when Rudolf II died of dropsy on January 20, 1612.

Matthias Habsburg

Matthias received only the appearance of power and influence. The finances in the state were completely upset, the foreign policy situation was steadily leading to a big war, domestic politics threatened another uprising, and the victory of the irreconcilable Catholic party, at the origins of which Matthias stood, actually led to his overthrow.

This sad inheritance went to Ferdinand of Central Austria, who was elected Roman Emperor in 1619. He was a friendly and generous gentleman to his subjects and a very happy husband (in both of his marriages).

Ferdinand II of Habsburg

Ferdinand II loved music and adored hunting, but work came first for him. He was deeply religious. During his reign, he successfully overcame a number of difficult crises, he managed to unite the politically and religiously divided possessions of the Habsburgs and began a similar unification in the empire, which was to be completed by his son, Emperor Ferdinand III.

Ferdinand III of Habsburg

The most important political event of the reign of Ferdinand III is the Peace of Westphalia, with the conclusion of which the Thirty Years' War ended, which began as an uprising against Matthias, continued under Ferdinand II and was stopped by Ferdinand III. By the time peace was signed, 4/5 of all war resources were in the hands of the emperor’s opponents, and the last parts of the imperial army capable of maneuvering were defeated. In this situation, Ferdinand III proved himself to be a strong politician, capable of making decisions independently and consistently implementing them. Despite all the defeats, the emperor perceived the Peace of Westphalia as a success that prevented even more serious consequences. But the treaty, signed under pressure from the electors, which brought peace to the empire, simultaneously undermined the authority of the emperor.

The prestige of the emperor's power had to be restored by Leopold I, who was elected in 1658 and ruled for 47 years after that. He managed to successfully play the role of the emperor as a defender of law and law, restoring the authority of the emperor step by step. He worked long and hard, traveling outside the empire only when necessary, and made sure that strong personalities did not occupy a dominant position for a long time.

Leopold I of Habsburg

The alliance with the Netherlands concluded in 1673 allowed Leopold I to strengthen the foundations for Austria's future position as a great European power and achieve its recognition among the electors - subjects of the empire. Austria again became the center around which the empire was defined.

Under Leopold, Germany experienced a revival of Austrian and Habsburg hegemony in the empire, the birth of the "Viennese Imperial Baroque". The emperor himself was known as a composer.

Leopold I of Hasburg was succeeded by Emperor Joseph I of Habsburg. The beginning of his reign was brilliant, and a great future was predicted for the emperor, but his undertakings were not completed. Soon after his election, it became clear that he preferred hunting and amorous adventures to serious work. His affairs with court ladies and chambermaids caused a lot of trouble for his respectable parents. Even the attempt to marry Joseph was unsuccessful, because the wife could not find the strength to tie her irrepressible hubby.

Joseph I of Habsburg

Joseph died of smallpox in 1711, remaining in history as a symbol of hope that was not destined to come true.

Charles VI became the Roman emperor, who had previously tried his hand as King Charles III of Spain, but was not recognized by the Spaniards and was not supported by other rulers. He managed to maintain peace in the empire without losing the authority of the emperor.

Charles VI of Habsburg, last of the Habsburgs in the male line

However, he was unable to ensure the continuity of the dynasty, since there was no son among his children (he died in infancy). Therefore, Charles took care to regulate the order of inheritance. A document known as the Pragmatic Sanction was adopted, according to which, after the complete extinction of the ruling branch, the right of succession was first given to the daughters of his brother, and then to his sisters. This document contributed greatly to the rise of his daughter Maria Theresa, who ruled the empire first with her husband, Franz I, and then with her son, Joseph II.

Maria Theresa at age 11

But in history, not everything was so smooth: with the death of Charles VI, the male line of the Habsburgs was interrupted, and Charles VII from the Wittelsbach dynasty was elected emperor, which forced the Habsburgs to remember that the empire is an elective monarchy and its governance is not associated with a single dynasty.

Portrait of Maria Theresa

Maria Theresa made attempts to return the crown to her family, which she succeeded after the death of Charles VII - her husband, Franz I, became emperor. However, in fairness, it should be noted that Franz was not an independent politician, because all affairs in the empire were taken into his hands tireless wife. Maria Theresa and Franz were happily married (despite Franz's numerous infidelities, which his wife preferred not to notice), and God blessed them with numerous offspring: 16 children. Surprisingly, but true: the empress even gave birth as if casually: she worked with documents until the doctors sent her to the maternity room, and immediately after giving birth she continued to sign documents and only after that could she afford to rest. She entrusted the care of raising her children to trusted persons, strictly supervising them. Her interest in the destinies of her children truly manifested itself only when the time came to think about the arrangement of their marriages. And here Maria Theresa showed truly remarkable abilities. She arranged the weddings of her daughters: Maria Caroline married the King of Naples, Maria Amelia married the Infante of Parma, and Marie Antoinette, married to the Dauphin of France Louis (XVI), became the last queen of France.

Maria Theresa, who pushed her husband into the shadow of big politics, did the same with her son, which is why their relationship was always tense. As a result of these skirmishes, Joseph chose to travel.

Francis I Stephen, Francis I of Lorraine

During his trips he visited Switzerland, France, and Russia. Traveling not only expanded the circle of his personal acquaintances, but also increased his popularity among his subjects.

After the death of Maria Theresa in 1780, Joseph was finally able to carry out the reforms that he had thought about and prepared during his mother’s time. This program was born, carried out and died with him. Joseph was alien to dynastic thinking; he sought to expand the territory and pursue the Austrian great-power policy. This policy turned almost the entire empire against him. Nevertheless, Joseph still managed to achieve some results: in 10 years he changed the face of the empire so much that only his descendants were able to truly appreciate his work.

Joseph II, eldest son of Maria Theresa

It was clear to the new monarch, Leopold II, that the empire would only be saved by concessions and a slow return to the past, but while his goals were clear, he had no clarity in actually achieving them, and, as it turned out later, he also did not have time, because the emperor died 2 years after election.

Leopold II, third son of Franz I and Maria Theresa

Francis II reigned for over 40 years, under him the Austrian Empire was formed, under him the final collapse of the Roman Empire was recorded, under him Chancellor Metternich ruled, after whom an entire era was named. But the emperor himself, in historical light, appears as a shadow bending over state papers, a vague and amorphous shadow, incapable of independent body movements.

Franz II with the scepter and crown of the new Austrian Empire. Portrait by Friedrich von Amerling. 1832. Museum of Art History. Vein

At the beginning of his reign, Francis II was a very active politician: he carried out management reforms, mercilessly changed officials, experimented in politics, and his experiments simply took the breath away of many. It was later that he would become a conservative, suspicious and unsure of himself, unable to make global decisions...

Francis II assumed the title of Hereditary Emperor of Austria in 1804, which was associated with the proclamation of Napoleon as Hereditary Emperor of the French. And by 1806, circumstances were such that the Roman Empire had become a ghost. If in 1803 there were still some remnants of imperial consciousness, now they were not even remembered. Having soberly assessed the situation, Francis II decided to relinquish the crown of the Holy Roman Empire and from that moment devoted himself entirely to strengthening Austria.

In his memoirs, Metternich wrote about this turn of history: “Franz, deprived of the title and the rights that he had before 1806, but incomparably more powerful than then, was now the true emperor of Germany.”

Ferdinand I of Austria "The Good" modestly ranks between his predecessor and his successor Franz Joseph I.

Ferdinand I of Austria "The Good"

Ferdinand I was very popular among the people, as evidenced by numerous anecdotes. He was a supporter of innovations in many areas: from the construction of the railroad to the first long-distance telegraph line. By decision of the emperor, the Military Geographical Institute was created and the Austrian Academy of Sciences was founded.

The emperor was sick with epilepsy, and the disease left its mark on the attitude towards him. He was called “blessed”, “fool”, “stupid”, etc. Despite all these unflattering epithets, Ferdinand I showed various abilities: he knew five languages, played the piano, and was fond of botany. In the matter of government, he also achieved certain successes. Thus, during the revolution of 1848, it was he who realized that Metternich’s system, which had worked successfully for many years, had outlived its usefulness and required replacement. And Ferdinand Joseph had the firmness to refuse the services of the chancellor.

During the difficult days of 1848, the emperor tried to resist circumstances and pressure from others, but he was eventually forced to abdicate, followed by Archduke Franz Karl. Franz Joseph, the son of Franz Karl, who ruled Austria (and then Austria-Hungary) for no less than 68 years, became emperor. The first years the emperor ruled under the influence, if not under the leadership, of his mother, Empress Sophia.

Franz Joseph in 1853. Portrait by Miklós Barabás

Franz Joseph I of Austria

For Franz Joseph I of Austria, the most important things in the world were: dynasty, army and religion. At first, the young emperor zealously took up the matter. Already in 1851, after the defeat of the revolution, the absolutist regime in Austria was restored.

In 1867, Franz Joseph transformed the Austrian Empire into the dual monarchy of Austria-Hungary, in other words, he made a constitutional compromise that retained for the emperor all the advantages of an absolute monarch, but at the same time left all the problems of the state system unresolved.

The policy of coexistence and cooperation between the peoples of Central Europe is the Habsburg tradition. It was a conglomerate of peoples, essentially equal, because everyone, be it a Hungarian or a Bohemian, a Czech or a Bosnian, could occupy any government post. They ruled in the name of the law and did not take into account the national origin of their subjects. For nationalists, Austria was a “prison of nations,” but, oddly enough, the people in this “prison” grew rich and prospered. Thus, the House of Habsburg really assessed the benefits of having a large Jewish community on the territory of Austria and invariably defended the Jews from the attacks of Christian communities - so much so that anti-Semites even nicknamed Franz Joseph the “Jewish Emperor.”

Franz Joseph loved his charming wife, but on occasion he could not resist the temptation to admire the beauty of other women, who usually reciprocated his feelings. He also could not resist gambling, often visiting the Monte Carlo casino. Like all Habsburgs, the emperor under no circumstances misses the hunt, which has a pacifying effect on him.

The Habsburg monarchy was swept away by the whirlwind of revolution in October 1918. The last representative of this dynasty, Charles I of Austria, was overthrown after being in power for only about two years, and all the Habsburgs were expelled from the country.

Charles I of Austria

The last representative of the Habsburg dynasty in Austria - Charles I of Austria and his wife

There was an ancient legend in the Habsburg family: the proud family would begin with Rudolf and end with Rudolf. The prediction almost came true, for the dynasty fell after the death of Crown Prince Rudolf, the only son of Franz Joseph I of Austria. And if the dynasty remained on the throne after his death for another 27 years, then for a prediction made many centuries ago, this is a minor error.

The national question and the crisis of the monarchy

The nature and characteristics of the revolutionary process in the Habsburg monarchy were determined by the large number of peoples inhabiting it and the contradictory nature of their socio-economic and political goals. In 1843, the territory of the empire was inhabited by a little more than 29 million people. Of these, 15.5 million were Slavic peoples, there were 7 million Germans, 5.3 million Hungarians, 1 million Romanians, 0.3 million Italians. Without forming a quantitative majority, the Austrians dominated the empire, discriminating against the Slavs of Bohemia directly subordinate to Vienna (Czech Republic), Galicia, Silesia, Slovenia, Dalmatia, Italians of the Lombardo-Venetian region. The Magyars of Hungary, seeking to restore their lost statehood and, therefore, being in a state of conflict with the Habsburgs, themselves suppressed the Rusyns of Transcarpathia, Slovaks, South Slavs of Croatia and Slavonia, the Serbs of Vojvodina, and the Romanians of Transylvania, who were made administratively dependent on them. In the lands of the Hungarian crown, the Magyars not only held the administrative apparatus in their hands, but also concentrated a significant part of land ownership, collecting feudal duties from the peasants.The inequality of the peoples of the empire put forward the objective task of national revival. Therefore, bourgeois transformations, which for Austria meant the destruction of the remnants of feudal economic relations and the transition from an absolutist to a constitutional form of government, in other parts of the empire led not only to the same result, but also to the establishment of their own statehood. The latter threatened the collapse of the Habsburg monarchy. It is not surprising that the Viennese court and Chancellor Metternich considered the inviolability of established foundations, bureaucratic management, unlimited police control over the activities of the intelligentsia and total supervision of the press to be the basis for preserving the empire. The suppression of glasnost went so far as to ban the publication of books with political content and the import of liberal works from England and France, even if they were not included in the index of prohibited books compiled by the Roman Curia.

The development of the state was hampered by ossified political structures. Since 1835, Ferdinand 1 was emperor, periodically plunging into severe depression. Under him, all affairs were in charge of the triumvirate (from the Latin triumviratus - three + + husband): the emperor's uncle Archduke Ludwig, Prince Metternich and Count Kolovrat. The rivalry between them made it impossible to make the necessary decisions. This had disastrous consequences for the monarchy, as the situation in the country became increasingly tense. Despite the police regime, the reform movement grew in the empire. The demands for their implementation were made by the bourgeois nobility, the bourgeoisie and the intelligentsia. These social strata were interested in capitalist transformations. Remaining moderately oppositional and liberal, they sought a transition to a constitutional monarchy, the abolition of feudal duties for ransom, and the abolition of guilds. The consolidation of reform supporters led to the creation of several organizations: the Political-Legal Club, the Industrial Union, the Lower Austrian Industrial Association, and the Concordia Writers' Union. Opposition literature was distributed in Vienna and the provinces.

Revolution of 1848 in Austria

In February 1848, when news of the revolution in France became known, muted fermentation grew into actions of direct pressure on the government. During March 3-12, a group of deputies of the Landtag of Lower Austria, which included Vienna, the Industrial Union, and university students presented, although at different times and separately, essentially similar demands: to convene an all-Austrian parliament, reorganize the government, abolish censorship and introduce freedom words. The government hesitated, and on March 13, the Landtag building was surrounded by crowds of people, slogans sounded: “Down with Metternich... Constitution... People's Representation.” Clashes initiated by people from the crowd with the troops entering the city began, and the first victims appeared. Things came to the barricades, and the students also created a paramilitary organization - the Academic Legion. Soon the formation of a national guard began from people who had “property and education,” i.e. bourgeoisie.The Academic Legion and the National Guard formed committees that began to actively intervene in the events that took place. The balance of forces changed, and the emperor was forced to agree to arm the bourgeois formations, resigned Metgernich and sent him as ambassador to London. The government proposed a draft constitution, but Bohemia (Czech Republic) and Moravia refused to recognize it. In turn, the Viennese committees of the Academic Legion and the National Guard regarded this document as an attempt to preserve absolutism and responded by creating a joint Central Committee. The government decision to dissolve it was followed by the demand, reinforced by the construction of barricades, for the withdrawal of troops from Vienna, the introduction of universal suffrage, the convening of a Constituent Assembly and the adoption of a democratic constitution. The government retreated again and promised to fulfill all this, but at the insistence of the emperor, it did the opposite: it issued an order to disband the Academic Legion. The inhabitants of Vienna responded with new barricades and the creation on May 26, 1848, of a Committee of Public Safety made up of municipal councilors, national guardsmen and students. He took upon himself the protection of order and control over the government's fulfillment of its obligations. The Committee's influence extended so far that it insisted on the resignation of the Minister of the Interior and proposed the composition of a new government, which included representatives of the liberal bourgeoisie.

The imperial court, powerless, was forced to resign itself. The emperor himself was not in Vienna at that time; on May 17, without even notifying the ministers, he left for Innsbruck, the administrative center of Tyrol. The Vienna garrison barely numbered 10 thousand soldiers. The main part of the army, led by Field Marshal Windischgrätz, was busy suppressing the uprising that began on June 12, 1848 in Prague, and then got bogged down in Hungary. The best troops in Austria, Field Marshal Radetzky, pacified the rebellious Lombardo-Venetian region and fought with the army of Sardinia, which tried to take advantage of the favorable moment and annex the Italian possessions of Austria.

Nothing could prevent the holding of elections to the first Austrian Reichstag; they took place and gave a majority to representatives of the liberal bourgeoisie and peasantry. This composition determined the nature of the laws adopted: they were repealed

feudal duties, and personal seigneurial rights (suzerain power, patrimonial court) without remuneration, and duties related to land use (corvee, tithe) - for ransom. The state undertook to reimburse a third of the redemption amount, the rest was to be paid to the peasants themselves. The abolition of feudal relations opened the way for the development of capitalism in agriculture. The solution to the agrarian question had the consequence that the peasantry moved away from the revolution. The stabilization of the situation allowed Emperor Ferdinand I to return to Vienna on August 12, 1848.

The last major uprising of the people of Vienna took place on October 6, 1848, when students from the Academic Legion, national guardsmen, workers, and artisans tried to prevent part of the Vienna garrison from being sent to suppress the uprising in Hungary. During street fighting, the rebels took possession of the arsenal, seized weapons, broke into the War Ministry and hanged Minister Bayeux de Latour from a street lamp.

The day after these events, Emperor Ferdinand I fled to Olmutz, a powerful fortress in Moravia, and Windischgrätz, pushing back the Hungarian revolutionary army rushing to Vienna, occupied the Austrian capital after three days of fighting on November 1, 1848. The critical situation allowed the upper echelons of power to achieve the abdication of Ferdinand in favor of his nephew Franz Joseph, who ascended the throne on December 2, 1848 and remained emperor for 68 years, until 1916. The imperial manifestos of March 4, 1849 dissolved the Reichstag and octroied (granted) a constitution, called Olmütz. It applied to both Austria and Hungary, was based on the principle of the integrity and indivisibility of the state, but was never applied in practice and was formally abolished on December 31, 1851.

Revolution of 1848-1849 in Hungary

The revolutionary wave in March 1848 also swept Hungary. At the beginning of the monththe leader of the noble opposition, Lajos Kossuth, proposed a program of bourgeois-democratic reforms to the Sejm. It provided for the adoption of the Hungarian constitution, reforms, and the appointment of a government responsible to parliament. Demonstrations and rallies in support of change began in Pest. On March 15, 1848, students, artisans, workers led by the poet Sandor Petőfi seized the printing house and printed a list of demands - “12 points”, among which one of the main ones were: freedom of speech and press, national government, withdrawal of non-Hungarian military units from the country and the return to the Hungarian homeland, the unification of Transylvania and Hungary.

The laws adopted by the Sejm, bourgeois in content, provided for the abolition of corvée and church tithes. Peasants who had corvee plots (and they made up about a third of all cultivated land) received them as property. The issue of ransom payments was postponed for the future. Although out of the 1.5 million peasants liberated by the revolution, only about 600 thousand became land owners, the agrarian reform undermined the feudal-serf system in Hungary. The constitutional reform preserved the monarchy, but transformed the country's political system, which was reflected in the establishment of a government responsible to parliament, the expansion of suffrage and the annual convening of the Sejm, the introduction of jury trials, and the establishment of freedom of the press. In the field of national relations, a complete merger with Transylvania and recognition of the Magyar language as the only state language were envisaged. On March 17, 1848, the first independent government of Hungary began its activities. It was headed by one of the opposition leaders, Count Lajos Batteanu, and Kossuth, who took the post of Minister of Finance, played an influential role in the cabinet. Emperor Ferdinand I (in Hungary he bore the title of King Ferdinand V) initially tried to repeal the laws adopted by the Diet, but mass demonstrations in Pest and in Vienna itself forced him to approve the Hungarian reforms in early April.

At the same time, the Hungarian nobility, for fear of losing their dominant position in the kingdom and the collapse of it itself, opposed national movements. Therefore, the government did nothing in the specific interests of the Slavic and Romanian territories of the Hungarian crown. The refusal to recognize their national equality, to provide self-government, and to guarantee the free development of language and culture turned the national movements that were initially sympathetic to the Hungarian revolution into allies of the Habsburg monarchy.

This trend turned out to be dominant in all non-Magyar lands subordinate to Hungary. Convened on March 25, 1848, the Croatian estate Sejm-Sabor developed a program that provided for the abolition of feudal duties, the creation of an independent government and its own army, and the introduction of the Croatian language in administrative institutions and courts. The response to the great power policy of Hungary, which deprived Croatia of any rights to autonomy, was the decision taken by the Sabor in June 1848 to recreate Croatian statehood in the form of the Croatian-Slavono-Dalmatian Kingdom under the supreme authority of the Habsburgs. The interethnic conflict led to a war with Hungary, which was started in September 1848 by the Croatian ban Josip Jelacic.

The Hungarian-Croatian clash did not end the ethnic contradictions. When Slovakia demanded to recognize the Slovak language as the official language, to open a Slovak university and schools, and to provide territorial autonomy with its own Sejm, the Hungarian government only intensified the repression. Regarding the national problems of the Serbs, Kossuth said that “the sword will decide the dispute.” Non-recognition of the rights of the Serbs led to the proclamation in May 1848 of the “Serbian Vojvodina” with its government and the subsequent attempt by the Hungarians to suppress the Serbian movement by force. The Austrian Habsburgs, having recognized the separation of Vojvodina from Hungary, turned this clash to their advantage. The Hungarian law on union with Transylvania, which recognized only the personal equality of its citizens, but did not establish national-territorial autonomy, and here provoked an anti-Magyar uprising that began in mid-September 1848.

Hungary's desire for independence caused sharp opposition from Emperor Ferdinand, who on September 22, 1848 made a statement regarded as a declaration of war. In order to better prepare for it, the Hungarians restructured their leadership: the Batteanu government resigned and gave way to the Defense Committee headed by Kossuth. The national army he created defeated Jelacic's troops, drove them back to the borders of Austria, and then itself entered Austrian territory. This success turned out to be short-lived. On October 30, the Hungarians were defeated in a battle near Vienna. In mid-December, Windischgrätz's army moved hostilities to Hungary and in January 1849 captured its capital.

Military failures did not force Hungary to submit. Moreover, after Ferdinand's abdication, the Diet refused to consider Franz Joseph as King of Hungary until he recognized the Hungarian constitutional order. The Hungarian constitution did not correspond to the ideas of the Viennese court about the state structure of the empire, and this, along with the Austrian internal political factors themselves, prompted Franz Joseph to consecrate, as already noted, the Olmütz Constitution. According to it, Hungary was deprived of all independence and transferred to the position of a province of the Habsburg Empire, which did not suit the Hungarian nobility and bourgeoisie at all. As a consequence, on April 14, 1849, the Diet of Hungary overthrew the Habsburg dynasty, proclaimed the independence of Hungary and elected Kossuth as head of the executive branch with the status of ruler. Now the Austro-Hungarian conflict could only be resolved by force of arms.

In the spring of 1849, Hungarian troops won a number of victories. Their commander, General Artur Görgei, is believed to have had the opportunity to capture virtually defenseless Vienna, but was bogged down in a long siege of Buda. Opinions are expressed that Görgei claimed the first role and, not being satisfied with the position of Minister of War and Commander-in-Chief, betrayed the cause of the revolution. Whether this is true or not, the Austrian monarchy received a respite, and Emperor Franz Joseph turned to the Russian Emperor Nicholas I with a request for help.

The invasion of Field Marshal Paskevich's 100,000-strong army into Hungary and a 40,000-strong corps into Transylvania in June 1849 predetermined the defeat of the Hungarian revolution. The hopelessly late law on the equality of the peoples inhabiting the Hungarian state was no longer able to help her. On August 13, 1849, the main forces of the Hungarian army, together with Görgei, laid down their arms. During the repressions, military courts handed down about five thousand death sentences. Görgei’s life was spared, but he was sent to prison for 20 years, but the head of the first government, Battyana, and 13 generals of the Hungarian army were executed. Kossuth emigrated to Turkey.

Results of the revolution of 1848-1849. in the Habsburg Monarchy

The defeat of the revolution led to the restoration of absolutism in the empire, but its restoration was not complete. The abolition of feudal duties was a major socio-economic transformation due to the emergence of a class of independent peasant owners. A return to the previous feudal order became impossible.At the same time, a period of severe reaction began in the national political sphere. The abolition of Austro-Hungarian dualism led to the subordination of Hungarian officials to a military and civil governor appointed by Vienna. The territory of Hungary proper was divided into five imperial governorships. Transylvania, Croatia-Slavonia, Serbian Vojvodina and Temisvár Banat, previously administratively subordinate to Hungary, were placed under direct Austrian control. Throughout the empire, police supervision was strengthened and a corps of gendarmes was created to oversee political reliability. The Law on Unions and Assemblies placed public organizations under the strictest control of the authorities. All periodicals were required to pay a deposit and submit one copy to the authorities an hour before publication. Retail sales and posting of newspapers on the streets were banned. The Germanization of the empire intensified. The German language was declared the state language and compulsory for administration, legal proceedings, and public education in all parts of the empire. The unresolved national and democratic problems throughout the subsequent time will constantly confront the empire with the need to overcome growing political crises until it finally collapses under their weight.